Illustration by Molly Mendoza.

Welcome to Savor the Science! In each Savor the Science, RENDER’s resident chemist, Claire Lower, will explore culinary questions through a scientific lens, perfecting recipes and demystifying techniques. Theories and reactions will be discussed and experiments will be performed; it’s like your high school chemistry class, only edible. Claire will take a scientific concept (such as the acid-base reactions in baking, macerating, or Maillard browning), explain it in a way that would make Bill Nye proud (hopefully), and then provide an edible experiment which allows you to demonstrate your new scientific food knowledge.

“Wait, did you say you bought some purple carrots?” my grandmother interrupts me to ask. She’s never seen or heard of such, and sounds slightly suspicious as I explain that carrots can come in many colors, but purple happens to be my favorite. “Well, that must be a West Coast thing; we don’t get those here.” (“Here” is northern Mississippi.)

If you do most of your food shopping at conventional grocery stores, you probably haven’t seen a purple carrot either. (Though some larger chains such as Trader Joe’s are starting to sell bags of the visually appealing roots.) They’re not super common, but purple carrots have been around longer than their orange counterpart.

According to a report by the BBC, the purple carrot dates back to “as far back as the 10th Century, the crop grew purple in India, the Middle East and Europe, with its origins traced to Afghanistan." Turns out that the orange-colored root we’re all so familiar with didn’t appear until the 17th century and is believed to have been bred in honor of the Orange-Nassau royal dynasty.

A carrot’s color isn’t just limited to orange and purple. There are yellow, red, and even white carrots, too. But what determines the color of a carrot, and does color have any influence on its taste or innate health benefits?

I’ve always thought that purple carrots were a little sweeter than their (boring) orange cousins, but that’s most likely all in my head. Though it’s possible for a purple carrot to be sweeter than an orange or yellow carrot, it’s also completely coincidental, as the chemical compounds responsible for the vegetable’s sweetness (primarily sugars such as glucose, fructose, and sucrose) are not what determine its color. Let’s explore the carrot rainbow, one color at a time, starting with the ubiquitous orange.

As a child, you were most likely told to eat your carrots for the sake of your vision. Orange carrots are high in beta-carotene, an unsaturated chain of carbon atoms that looks like this:

Image source "BetaCarotene-3d" by Sbrools - Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Due to its intense yellow-orange pigment, it’s very easy to spot fruits and vegetables with high concentrations of beta-Carotene. Pumpkins, sweet potatoes, cantaloupes, and peppers all contain a good bit of the stuff. Dark leafy greens also contain large amounts of the pigmented hydrocarbon, which in this case is overshadowed by chlorophyll. (You can see beta-Carotene better in autumn, when the the chlorophyll in the leaves begins to break down and the beta-Carotene in leaves becomes visible.) When you eat orange carrots (or any plant matter high in beta-Carotene), your body converts it to vitamin A to the benefit of your skin, bones, and eyes.

Yellow carrots get their color from lutein, an organic carotenoid closely related to beta-Carotene. Like its orange cousin, lutein is also beneficial to your eyes and, according to WebMD, is “thought to function as a light filter, protecting the eye tissues from sunlight damage.”

Red carrots possess lycopene, a bright red carotenoid also found in tomatoes, strawberries, and bell peppers. Like lutein, lycopene is also structurally similar to beta-Carotene, though neither produce any vitamin A. Lycopene is a powerful antioxidant, which is why some researchers are looking to it as potential cancer prevention.

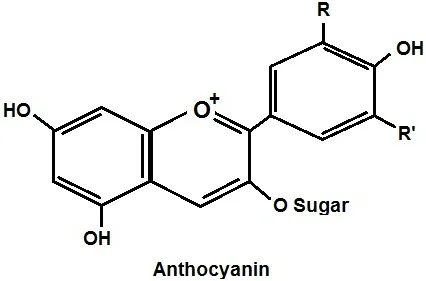

Purple carrots are made beautiful by anthocyanins, which we talked about briefly during our discussion of quinces. Anthocyanins look nothing like carotenoids on a molecular level, possessing more rings of carbon than chains.

These water-soluble pigments can appear blue, red, or purple depending on the pH of their environment. They appear pinkish in acidic environments, purple in neutral, and greenish-yellow in basic. Not only are they beautiful, but anthocyanins’ antioxidant properties may help prevent heart disease.

And there are white carrots, which possess their own sort of stark beauty, though no pigmented carotenoids nor anthocyanins. (They may possess a very small amount of carotenoids, but not enough to be a significant dietary source). This makes them the “least healthful” member of the carrot rainbow, but they’re still a good source of fiber and phytochemicals, and their mild flavor may be more favorable to some.

No matter what color you choose, the carrots natural sweetness makes it an easy ingredient to work with. I like to roast mine and let those sugars break down and caramelize, so that the flavors intensify and the texture becomes velvety. My favorite fat for this application is rendered duck fat; it takes any roasted vegetable to a totally new, indulgent level.

Duck Fat-Roasted MultiColored Carrots

Ingredients:

6 carrots of whatever colors you love most, peeled and cut on a bias

1 ½ Tablespoons of duck fat

¾ teaspoon salt

¼ teaspoon freshly ground pepper

¾ teaspoons minced garlic

Preheat the oven to 400F. Combine all ingredients in a resealable plastic bag and shake until all carrot pieces are coated. Spread carrot pieces out on a baking tray or foil-lined baking sheet and roast for 30-40 minutes, until carrots are tender on the inside and crisp on the edges.