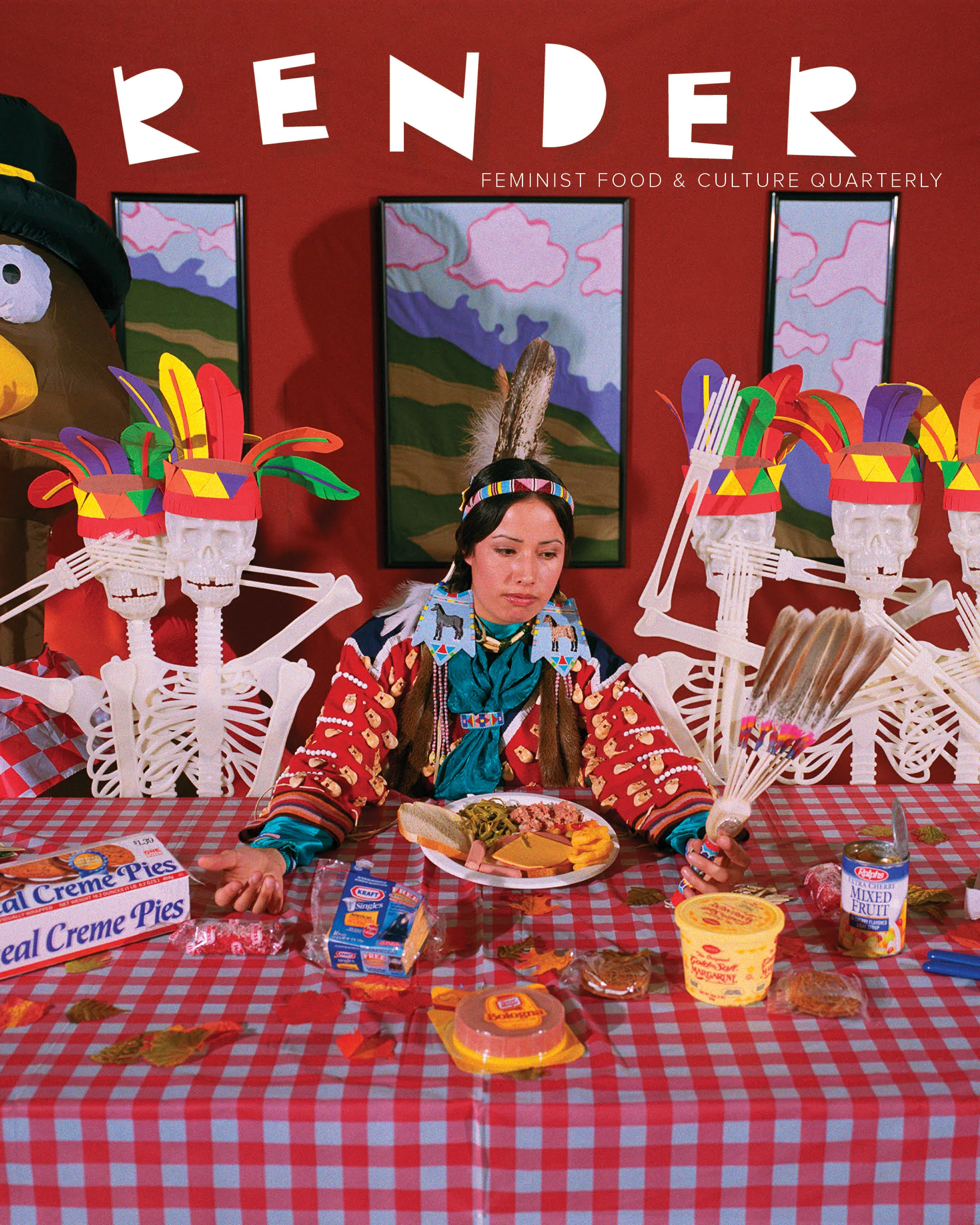

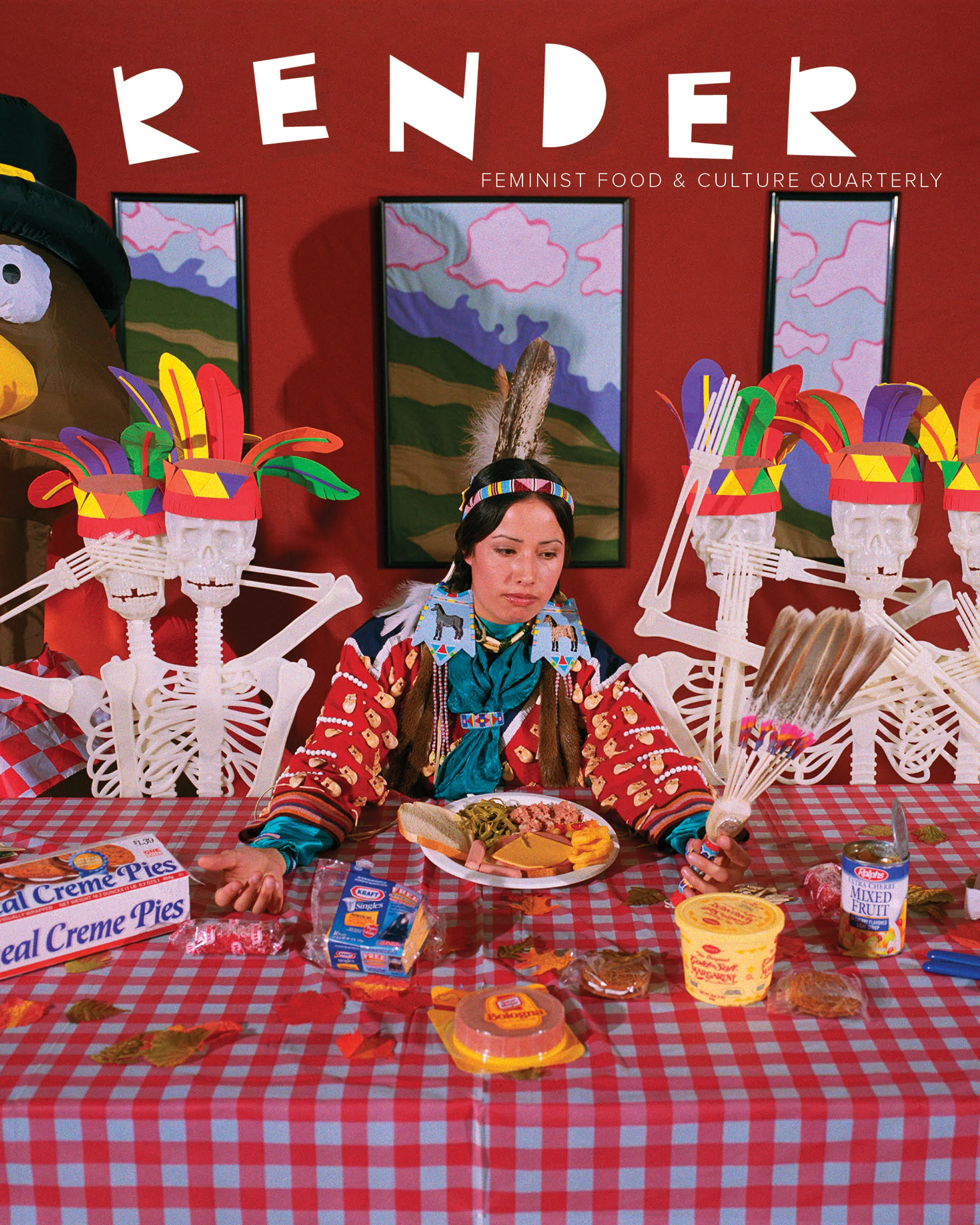

Illustration by Cate Andrews.

This piece is forthcoming in our TIMING issue, due out at the beginning of April. Pre-order your copy of the print or digital issue.

This past October, I was invited to participate in a competition for young chefs hosted by Ment’or BKB, an organization helmed by chefs Jérôme Bocuse, Thomas Keller, and Daniel Boulud. As “ambassadors of quality and excellence in the world of gastronomy,” we competitors were fêted and complimented, embraced and toasted by seasoned chefs at Bouchon Bistro in Beverly Hills, where the competition took place.[i] Altogether, the seven men who made up the panel of judges represented more than a century’s worth of experience, notwithstanding the storied French culinary traditions that they had helped bring into the present day. They told us that this was the start of something big and important for us and the industry, and it was hard not to believe them. And, as I stood onstage with them, dressed in a crisp white chef’s jacket and flashing a photo-friendly smile, all I could think was, “I am going to eat all of your livers.”

Months earlier, my chef had gathered the kitchen crew together after service (all of us younger than thirty-five), locked eyes with each of us, and told us to grow up, to take responsibility for our own educations and careers, and to respect our roles as craftspeople within the food industry. It all felt pretty standard as far as pep talks went, but then he said, “I want you to kill me and eat my liver.” We all laughed uneasily. I thought fleetingly about how eating the fatty, iron-rich liver could be both a mark of opulence as well as poverty, and I thought about the generations of cooks who learned through accident and hard work to transfigure unappealing organ meat into beautiful things like foie gras, pate, and boudin. Until that point, everything that I’d heard – both within the food industry and the greater world of creative work – adhered to the tenet that, in order to succeed, one had to pay one’s dues and lay at the feet of the masters before even attempting to put a word in edgewise. You can see this in the way the glassy-eyed apprentice in the documentary Jiro Dreams of Sushi recounts his experience of making tamagoyaki for months before being acknowledged as a cook by his master.[ii] I saw this in the crowd’s breathless, almost Beatlemaniacal fawning over Chef Keller as he walked through the palatial dining room of Bouchon Bistro. Just over a year ago, TIME Magazine’s food-centric issue lauded the “Gods of Food,” whose “otherworldly” influence over the industry was said to surpass the reach of mere mortals.[iii] The message of all this is plain to see: bow down, bitches.

Up until recently, that culture of hero worship was status quo for me: I had my own geeky list of chef gods and goddesses, and made a habit of flipping through their glossy cookbooks in the hopes that my fingertips could absorb some of their divinity. I would try to picture myself at high-end food festivals, doling out on-trend hors d’oeuvres while talking shop with the press. As a young woman of color in the food industry, I was all too eager to assimilate in order to further my career: I much preferred the idea of becoming a Stepford chef than an untidy “ethnic” cook. The contradictions of my position would quietly pull at me, especially as I began to learn more about the industry’s demons.

The culture of the modern food industry is a two-faced one. On one hand, we know and experience it as something centered on blue collar life, on a rough-and-tough lifestyle choice that comes through in images of comfortable machismo and veggie tattoos, in the foodie’s hunt for mom-and-pop authenticity in the barrios and ghettos of our cities. “We are artists, pirates,” says Colette, the only female chef de partie in Pixar’s Ratatouille, one of the more realistic depictions of kitchen life in film.[iv] Many of us who are still early in our careers are well aware of the realities of trading our daylight hours and weekends for what amounts to a modest wage, sore feet, and the occasional shift drink.

On the other hand, young cooks and chefs are increasingly being called upon to do more with ourselves: cooking alone won’t cut it if you’re serious about your passion. In 2011, the G9, the (all-male) advisory board of the Basque Culinary Institute that is chaired by Chef Ferran Adrià and whose membership rolls include the world’s most influential chefs, issued its “Open Letter to the Chefs of Tomorrow,” which called upon the next generation chef to be “socially engaged, conscious of and responsible for his or her contribution to a fair and sustainable society.”[v] The letter, signed by the definitive who’s who list of the culinary world, asks young chefs to seek out sustainable foods, contribute to our communities’ economic betterment, address public nutrition issues, and let our personal ethics lead us through our careers, among many other recommendations. Many chefs and industry personalities have answered the call, participating in, or fervently following, Chef René Redzepi’s international MAD symposium, writing informal essays and feature pieces for Eater.com and Lucky Peach, watching and discussing food documentary shows and films, and doing more research into their local food purveyors.

Within this uplifting and lifestyle-affirming context, it’s strange for me, line cook pond scum that I am, to even fathom the idea of besting veteran chefs in pan-to-pan combat and consuming their offal. But how could I not want to? If the G9 wants young chefs to wake up to real-world issues of environmental sustainability, labor rights, and the meaning of our place in human society, they should also be prepared for us to look inward, towards the industry they helped build. As it stands, their world of haute cuisine is everything that the chef of tomorrow shouldn’t aspire to: top-tier restaurants flaunt ingredients with hefty carbon footprints that must be flown across the world like bluefin tuna and truffles; for-profit culinary schools contribute to the impending and potentially catastrophic student loan bubble; and, most frustratingly, it is clear that for all of the bombastic calls for change from idealistic chefs, anything that trespasses against the restaurateur’s profit motive is off-limits. The conscious young chef of today – the millennial chef – might not look so kindly upon the world that the chef of yesterday built. Rather than depending on the old school’s sense of noblesse oblige to define our relationship to our craft, we owe it to ourselves and to the tremendous amount of faith placed in us to eat liver—that is, to pull the “Gods of Food” from their pedestals and decide that we can do more than flail at improving upon their model along the guidelines they’ve specified.

The chefs of tomorrow should be free to decide on their own what being a respectable chef looks like and will look like in the future. Are we happy with inheriting the traditional brick-and-mortar restaurants, the brigade system, the hotels, the cruise ships, the cults of personality, the resort town festivals, the culinary schools, the Syscos and Aramarks, the corporation-sponsored rankings and lists? Our mentors, the chefs of yesterday, deserve respect for their hard work, but it is young chefs’ obligation to do more than unquestioningly take up their mantles if we truly want to take ownership of our own ethics and our craft.

Soleil Ho is a “chef of tomorrow” who works in the intensive fine dining trenches in New Orleans, LA. Her nonfiction writing has appeared in Bitch, Interrupt Mag, the Atlas Review, Render, and more. Find more of her writing at http://soleilho.tumblr.com.

[i] Ment’or BKB, Our Mission, http://www.mentorbkb.org/about/ (Nov. 1, 2014).

[ii] Jiro Dreams of Sushi, directed by David Gelb (2011; New York, NY: Magnolia Pictures), Stream.

[iii] Howard Chua-Eoan, “The 13 Gods of Food,” Time, Nov. 17, 2013 (http://time100.time.com/2013/11/07/the-13-gods-of-food/).

[iv] Ratatouille, directed by Brad Bird (2007; Hollywood, CA: Disney), Stream.

[v] Luciana Bianchi, “Chefs' G9: the 'Lima Declaration,'” Fine Dining Lovers, https://www.finedininglovers.com/blog/news-trends/chefs-g9-lima-declaration/ (Nov. 1, 2014).