Welcome to Savor the Science! In each Savor the Science, RENDER’s resident chemist, Claire Lower, will explore culinary questions through a scientific lens, perfecting recipes and demystifying techniques. Theories and reactions will be discussed and experiments will be performed; it’s like your high school chemistry class, only edible. Twice a month, Claire will take a scientific concept (such as the acid-base reactions in baking, macerating, or Maillard browning), explain it in a way that would make Bill Nye proud (hopefully), and then provide an edible experiment which allows you to demonstrate your new scientific food knowledge.

Humans are strange.

We are oddly dogged when it comes to eating things that a less persistent species would have given up on after a couple of bites. Think of the olive. Who plucked an olive fresh from the tree, gave it a few chews, and said “This is disgusting; let’s soak it in a bunch of stuff and then eat it”?

Some genius, that’s who.

There are numerous fruits and vegetables the sight of which alone should have deterred us from eating them. Celery root is hideous (most roots are). Potatoes (another root) are a little dodgy. The pineapple is physically uncomfortable to hold, but we push through the pain, disarming its defenses so that we might consume its delightfully sweet flesh.

Not even (small-scale) chemical warfare can deter us.

The biological bomb unleashed by the onion has been a literal pain in the eyes from the moment it was first dug up. Armed with sulfurous compounds, the onion has a built-in gas attack ready to deploy at a moment’s notice. The only activation code required is your chef’s knife.

They never meant to start a war.

It’s hard to blame the onion for trying to defend itself. The compounds responsible for that horrible burning in your eyes aren’t even present in the onion until you cut, peel, or otherwise damage the onion’s cellular walls. By breaking the flesh, you are freeing enzymes (called alliinases, named after the genus Allium, to which the onion belongs) from their storage vacuoles, allowing them to combine with various free-floating compounds to produce a wide range of new chemicals (McGee 1984, 310-311).

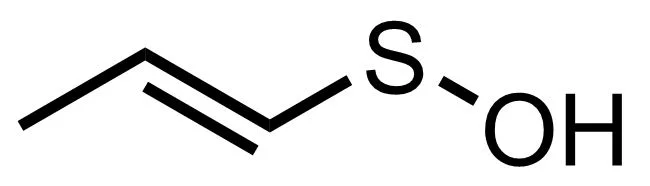

One of these new compounds is 1-propenesulfenic acid, a sulfur-containing organic acid that looks like this:

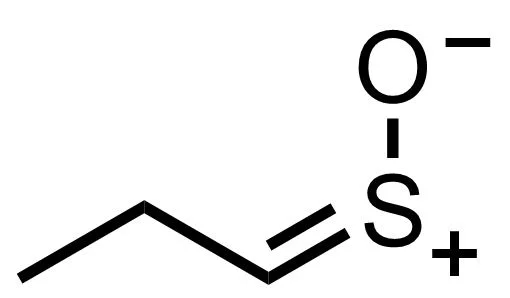

It doesn’t hang around long, but is quickly rearranged by a second enzyme to give us syn-Propanethial-S- oxide. This, my friends, is the gas that wafts up towards your eyes, irritating the nerve endings in your cornea and activating a defensive wave of tears. It looks like this:

Though there are many tips and tricks for preventing the tears brought on by chopping onions, the main aim is to keep the gas from getting to your eyes. You can either physically shield them with a pair of swim goggles or those that are specifically marketed as “onion goggles”—or you can move the gas away from you. This can be accomplished by working near a running fan or cutting the onions under running water, though the latter seems pretty impractical and not very safe.

Heating or cooling the onions before chopping may help to denature or slow the enzymes, respectively. However, heating isn’t a viable option if you plan to use them in their raw, most abrasive form.

A sharp knife also helps; a dull blade will crush those vacuoles on its way through the onion, releasing more gas than a clean cut would.

My method of choice is to work as quickly as possible and then run from the room to rinse my hands and eyes. The pleasure is worth all the pain. These sulfur-containing compounds may be a bit uncomfortable, but they are also responsible for the onion’s delightfully pungent flavor, a flavor that was supposed to be a deterrent.

Like I said, humans are weird. The very chemical defenses that plants employ to make themselves undesirable are an added bonus as far as we’re concerned. We enjoy the mild damage done to the unprotected cell membranes of our mouths and nasal passages and – in an effort to sound less masochistic – we call it “pungency.”

“Pungency” isn’t really a flavor. Pungency is “a general feeling of irritation that verges on pain.” That sounds pretty unpleasant, but you know you like it. My guess would be that it makes you feel alive and Psychologist Paul Rozin agrees. According to On Food and Cooking, Rozin posits:

“Perhaps spicy foods are the edible equivalent of riding a rollercoaster or jumping into Lake Michigan in January, an example of 'constrained risk' that sets off uncomfortable warning signals in the body. But since the situations are not truly dangerous, we can ignore the normal meaning of these sensations and savor the vertigo, shock, and pain for their own sakes” (McGee 1984, 394).

But all this talk or pain and pungency detracts from the onion's sweet side. Though it starts out harsh, an abundance of sucrose (table sugar) chains break down during cooking, leaving us with one of the most delicious burger toppings of all time: caramelized onions.

When onions are heated, their sucrose breaks up into glucose and fructose, and then those sugars break down further and recombine to form molecules that are responsible new colors, tastes, and smells. In addition to caramelization of sugars, our old friend Maillard browning is also in play with those sulfur-containing amino acids. Though there are hundreds of complicated reactions and transformations occurring on the molecular level when you brown onions, all you really have to worry about is not burning them. The result is something that is savory, sweet, and a little pungent all at the same time.

Add a little extra sugar and some vinegar and you can make a quick onion jam to serve with sharp cheeses, rich meats, or mixed into some sour cream for a delicious onion dip.

Easy Caramelized Onion Jam (Adapted from Hugh Acheson’s recipe on Food & Wine)

3 onions (I used two sweet and one yellow)

1⁄4 cup of olive oil

2 bay leaves

1⁄2 cup of red wine

1 cup of sugar

3⁄4 cup red wine vinegar

Using your preferred method of eye protection, halve onions and then slice thinly. In a large pot or Dutch oven, heat olive oil over medium-high heat until it begins to simmer, and add onions. Cook until they are golden brown (about 15 minutes).

Add bay leaves and cook for a couple of minutes until fragrant. Add wine and let cook until the liquid has almost completely reduced, stirring to incorporate.

Sprinkle sugar over onions and allow to melt completely without stirring. Increase the heat to high heat and let cook undisturbed until a thick caramel begins to form (about 6 minutes). Stir, add vinegar, and cook until jam thickens, stirring to prevent burning.

Serve in any of the aforementioned ways, or do what I did for lunch and cook into a grilled cheese.

There’s really no wrong way to eat this stuff.

Further reading:

Harold McGee. 1984. On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen. (New York: Scribner)