Welcome to Savor the Science! In each Savor the Science, RENDER’s resident chemist, Claire Lower, will explore culinary questions through a scientific lens, perfecting recipes and demystifying techniques. Theories and reactions will be discussed and experiments will be performed; it’s like your high school chemistry class, only edible. Twice a month, Claire will take a scientific concept (such as the acid-base reactions in baking, macerating, or Maillard browning), explain it in a way that would make Bill Nye proud (hopefully), and then provide an edible experiment which allows you to demonstrate your new scientific food knowledge.

The cranberry can take on many forms: sauce, relish, jellied mold. It’s not important how the cranberry gets to the table during the holidays, just that it gets there. Like potatoes, everyone seems to have their favorite iteration. Some prefer a homemade sauce, others insist that Thanksgiving cannot begin unless their sauce has can lines. All sauces have the same ingredients, but the consistency can vary greatly. What determines the shape and viscosity, and what separates a viscous sauce from a sliceable mold?

The answer lies in polymerization, specifically the polymerization of pectin.

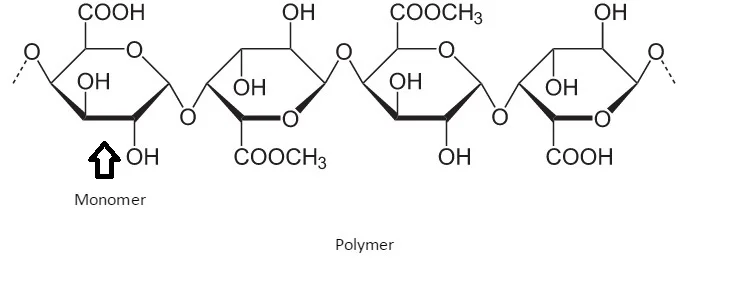

Polymers are long chains of repeating molecular subunits called monomers. Pectin is a naturally occurring polymer found in the primary cell walls of plants. It acts as a kind of cement, holding the cell walls together.

Pectin is often purchased in powdered form and used to promote the gelling of jellies and jams made from fruit with low pectin levels, but that’s unnecessary when working with firmer fruits with higher levels of pectin. When making jams and jellies, pectin works with acid and sugar to form stable gels. In addition to breaking down cell walls, acid also works with the pectin to form insoluble fibers. Sugar stabilizes by binding up some of the water, keeping your gel from losing water through “weeping.”

Cranberries, along with apples and citrus peels, naturally contain a lot of pectin. When heated, the cell walls of the fruit begin to break down, and the cranberries pop open. Their pectin is released and the long polymer chains begin to interact and tangle, stabilizing the sauce by trapping dissolved sugars and juices. The longer the cranberries are heated, the more pectin is extracted, and the firmer the sauce becomes.

Most homemade cranberry sauces are on the saucier side. You could add some powdered pectin, but why not add some other high-pectin fruits, like apples and oranges?

Fresh cranberries contain somewhere between 0.4 and 1.2 percent pectin. Whole, green apples contain 1-1.5 percent, but their pomaces (the parts leftover after juicing) contain 10-15 percent. Whole-orange pectin content is in the range of 0.5-3.5, but the peel contains an impressive 20-30 percent.

Given that apples and oranges both contain higher levels of pectin than cranberries, adding them should increase the overall pectin content of your sauce and help with gelling. At least that’s the idea behind this recipe (which uses apples) and this article (which recommends the use of a quartered orange).

That sounds reasonable enough, but given that (from a chemistry perspective) food is one of the most varied chemical systems around, each claim needed to be tested.

For a baseline, I started with the basic Ocean Spray 3-ingredient recipe, which produces a delicious, more liquid than jellied sauce.

Ocean Spray Fresh Cranberry Sauce (Adapted from OceanSpray.com)

Ingredients:

1 cup sugar

1 cup water

1 12-ounce package fresh cranberries

Instructions:

Add sugar and water to a medium saucepan. Bring to a boil and add in the cranberries. Return to a boil. Reduce heat and boil gently for 10 minutes, stirring occasionally. Remove from heat and pour into suitable container. Let cool to room temperature and refrigerate until the turkey is ready.

I then repeated this recipe three more times, introducing a different variable with each. To test the “apple theory,” I diced a firm green apple into ½-inch pieces (core and all) and added it to the sauce at the same time as the cranberries, removing them at the end. Unlike the Food & Wine recipe, which recommends a longer cooking time of at least 15 minutes so that the cranberries completely breakdown, I stuck to the original 10-minute simmer time. By only varying one component (adding the apple), we are able to see if it is indeed the pectin in the apple, and not the increased cooking time, that helps the sauce gel.

To test the “orange theory,” I did essentially the same thing, changing nothing about the process except the addition of the quartered orange.

Lastly, I decided to see if increased cooking time would promote gelling, the idea being that the longer the cranberries cooked, the more they would break down, releasing greater amounts of pectin into the sauce. I used the Ocean Spray recipe once more, this time changing no variables except cooking time, which I doubled to 20 minutes.

Results:

Like every experiment I have ever done in any lab, the results were not what I expected.

The baseline recipe (no added fruits, 10-minute cooking time) gelled together pretty well, loosely holding its form:

Not bad at all.

The sauce I added the orange to just barely held its form:

Trying so hard to keep it together.

The sauce with the chopped apple was a complete mess:

Disaster.

I know that looks pretty terrible. Here, let’s put it in a bowl.

Much better.

The only portions of apple and orange sauces that truly congealed were a thin skin on the top.

Skin taken off the top of the cran-orange sauce.

The plain cranberry sauce with the 20-minute simmering time gelled beautifully.

Just look at it.

Based on the outcome of each recipe, I feel pretty comfortable saying that the addition of other pectin-containing fruits does not help with the gelling process. In fact, it seems to hinder it.

How can this be?

First, by adding more fruit to a recipe, you are adding more water. All three fruits are over 80 percent water. When you cook them, they’re not only giving up pectin—they’re releasing water as well, diluting the sauce and altering the intended ratio of sugar-water-pectin.

According to the Cape Cod Cranberry Growers' Association, “Cranberries will gel at about 30% sugar. You see, they need to grab all of the water away from the pectin so that the pectin molecules can bond with each other, instead of the water.” In our experiments above, the apples and oranges increased the water content, but the amount of sugar remained the same. This could account for the poor gelling with these two recipes.

Another factor that may have affected the gelling is pH. Cranberries are more acidic and therefore have a lower pH than apples or oranges. As a result, they require less sugar when forming gels. By introducing these fruits, the pH may have shifted slightly higher, and those insoluble fibers may not have formed as well. A little added lemon juice would have helped take it back in the right direction.

The above experiments demonstrate an important point: food is very chemically complicated. What may seem like a simple alteration (for example, the addition of a chopped apple), may introduce a number of unanticipated chemical reactions. With an extended cooking time, added acid, or less water, a cranberry sauce containing apples could gel successfully, but it’s not as easy as just chucking in an apple. You’ll extract some extra pectin, but you’ll also extract thousands of other compounds, including water.

If you want a delicious cran-apple sauce for Turkey Day, it may be worth tinkering with. But if you simply want a firm, well-gelled cranberry sauce, all you need to do is double the cooking time to extract more pectin.

Oh, and if your aunt really needs the can lines, you can always use an empty can as a mold.