Illustration by Molly Mendoza.

Welcome to Savor the Science! In each Savor the Science, RENDER’s resident chemist, Claire Lower, will explore culinary questions through a scientific lens, perfecting recipes and demystifying techniques. Theories and reactions will be discussed and experiments will be performed; it’s like your high school chemistry class, only edible. Twice a month, Claire will take a scientific concept (such as the acid-base reactions in baking, macerating, or Maillard browning), explain it in a way that would make Bill Nye proud (hopefully), and then provide an edible experiment which allows you to demonstrate your new scientific food knowledge.

Halloween means different things to different people.

For some, Halloween means watching old scary movies, eating candy that you bought for trick-or-treaters, and drinking while dressed in a costume that nobody gets because once again, you have decided to go as something clever that hasn’t been relevant for ten to fifteen years.

All of that is delightful.

Unfortunately, Halloween also means having to endure “sexy” versions of beloved childhood characters (like this off-brand Mickey Mouse) and deeply troubling displays of cultural appropriation.

Hopefully, none of your friends are guilty of such shenanigans. However, if you find yourself in the company of problematic, Halloween-related behavior, it’s nice to be able to turn to the comforts of candy and alcohol.

For the sake of efficiency, why not combine the two?

You could make candy corn Jell-O shots, but that’s fairly labor intensive. You could make alcoholic marshmallows, but that requires a candy thermometer and results in a sticky mess. For an alcoholic treat that requires little prep work and almost no clean up, I recommend booze-soaked gummy candy.

Step into my laboratory.

The Theory:

Gummy candy is usually made with equal parts sucrose (table sugar) and corn syrup and a mixture of gelatin and pectin (McGee 1984, 686). Gelatin is derived from collagen, the main component of animal connective tissue that helps hold our bodies together and prevents our organs from sloshing around in a sack of skin. (Collagen gives your skin its fairly elastic texture as well; we have a lot to thank collagen for).

Once extracted from some sort of animal byproduct, gelatin is primarily used as a gelling agent in cooking. This probably conjures up images of sweet treats such as gummies, Jell-O, and marshmallows, but gelatin is also used as a stabilizer for things like cream cheese and margarine, and can be used in low-fat foods to give them the creamier mouthfeel that the removed fat would usually provide.

Gels are bizarre because they appear solid, but are actually mostly liquid by weight. When using gelatin, its long molecules get tangled with each other, trapping liquids such as water (or alcohol) in a network of gelatin “strands” that restrict the movement of liquid and cause the gel to behave as a solid.

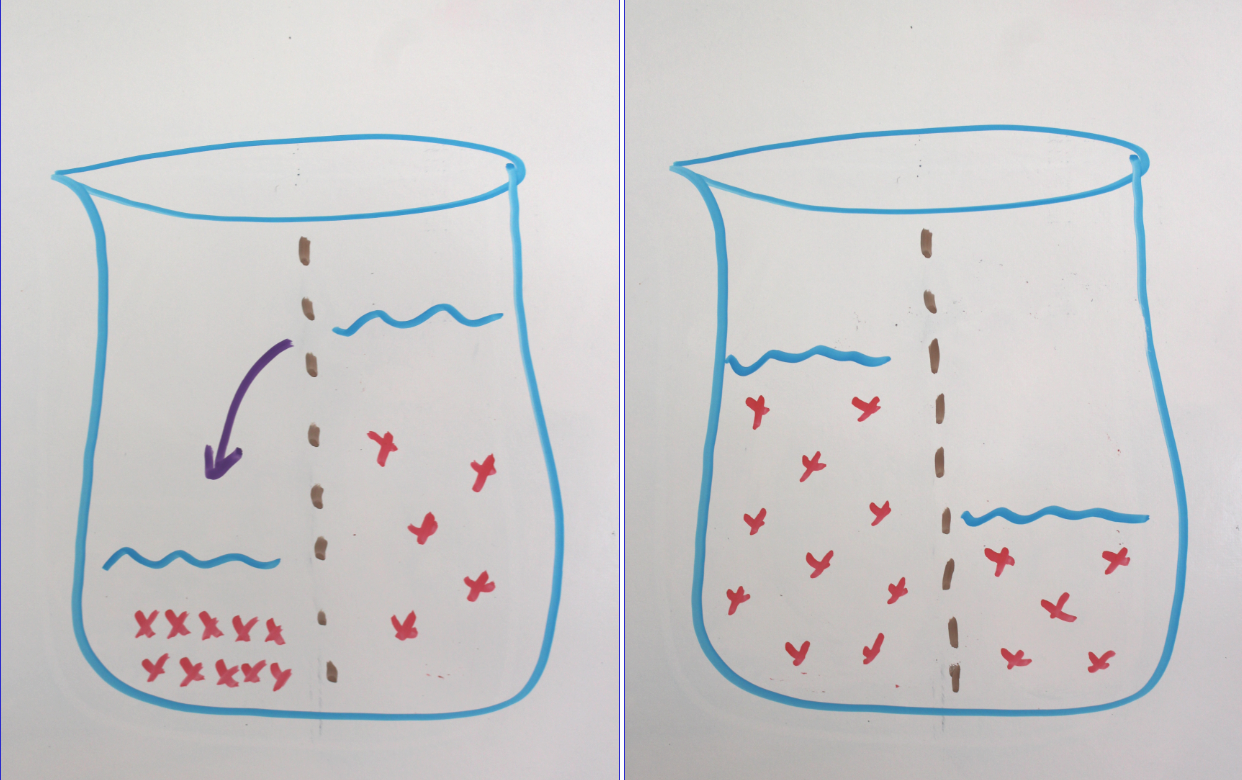

By allowing gummy bears to bathe in booze, you are creating an opportunity for osmosis. We’ve covered osmosis before (when we made delicious macerated strawberries) but just to recap:

In chemistry, a solution is defined as a mixture of one substance dissolved in another. The substance that does the dissolving is called the “solvent” and the substance that is dissolved is called the “solute.”

Osmosis is the movement of the solvent across a semipermeable membrane from an area of lower solute concentration to an area of higher solute concentration in an attempt to equalize the concentration on both sides.

Since gummy bears are full of delicious solvents (mainly sugar), your ethanol of choice will flow into the bear, where it will get trapped by gelatin. The bear will swell and hold its liquor until you mash it up in your chops.

The Tricky Part:

Though the gelatin in the candy will act as a stabilizer for you treats, it must be noted that ethanol is a powerful solvent. According to the folks at Molecule-R, gelatin retains its properties in solutions that are up to 40% ethanol (or 80 proof). So while most of the recipes you see floating around on Pinterest recommend the use of vodka in the pursuit of boozy heaven, your journey will be much more pleasant (and less slimy) if you choose a liquor with a lower ABV.

If you simply must use the strongest stuff, make sure you let your candy steep in the fridge, as cold temperatures decrease gelatin solubility.

The Experiment:

But enough with theory, let’s experiment a bit. Though I had been warned by science that vodka would wreck my candy, I wanted to see it with my own eyes. Also, with so many seasonal candy offerings, it would be a shame to limit the experiment to gummy bears.

My test subjects.

I selected a bag of assorted body parts, witch fingers, snakes, oozing skulls, gummy bears, and some Sour Patch Kids, just to see what would happen. (Sour Patch Kids don’t contain any gelatin so the results were a little terrifying).

Why is it smiling?

To establish a baseline, I first soaked the plain gummy bears in vodka and weaker—24% ABV— (but more flavorful) Campari. I let both sit for 24 hours at room temperature.

Happy Campari-soaked gummy.

The Campari-soaked bear, pictured above, was wildly more successful; it swelled quite visibly whereas the poor bear soaked in vodka lost all of his features to the much stronger solvent.

The Campari bear also tasted of Campari, which is a huge plus. It was like taking a tiny chewable shot.

To test my theory about temperature, I tried the vodka-bears again. This time I let them sit in the fridge overnight. The results were much more pleasing, though Campari is still the more flavorful option.

But gummy bears don't represent all gummy candies. Each specimen most likely has a different gelatin content, so I decided to test each type in vodka, just to see how they held up.

Spoiler: They held up poorly. After four hours of soaking at room temperature, the candies had undergone the following (startling) transformations:

Witch fingers.

Eyeballs!

Oozing skulls, now with more ooze!

Gummy snakes!

Rather than swelling, each candy simply disintegrated. They may not look that fragile in the above photos, but just look at what happened to the witch finger when I tried to pick it up and eat it:

Horrifying.

I tried the same experiment in the fridge, but the results were pretty much the same, if colder. I tried them in the Campari and they seemed to do much better in the swelling department, though they were slimier than the bears.

The Campari had the added benefit of making the witch finger look 100x more spooky.

Why the Difference?

Though each of these candies contained gelatin, it’s impossible for me to determine exactly how much gelatin. However, based on the fact that the gummy bears were much firmer than any of the other gelatin-based candies, I suspect that the bears contained the largest amount, resulting in a much tougher network of gelatin molecules, rendering them less soluble than the softer candies.

About Those Sour Patch Kids

As mentioned earlier, Sour Patch Kids (and Swedish Fish) contain no gelatin, relying instead on cornstarch as a thickener. Though the starch does swell when introduced to liquid, the texture of these booze-infused children becomes mealy and grainy, so it’s best to stick to candies that contain gelatin.

I was really excited until I bit into it.

Conclusions:

Of the booze-soaked candies I tested, the gummy-bear-and-Campari combination was the clear winner. This doesn’t mean that you can only use gummy candy shaped like bears, or that Campari is the only acceptable booze. But you should start with a tougher, gelatin-based candy, and choose a liquor that is relatively low in ethanol—aim for no more than 25-30% ABV.

Feel free to experiment, but remember that gelatin content, alcohol percentage, and temperature all play a part in how quickly your candies will infuse and/or dissolve.

On a side note, Savor the Science will be taking a short break for the rest of the month, but will be back in November with new, exciting recipes and experiments to educate and satiate. Until then, have a happy Halloween and I’ll see you in a couple of weeks!

References:

Harold McGee. 1984. On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen. (New York: Scribner), 686