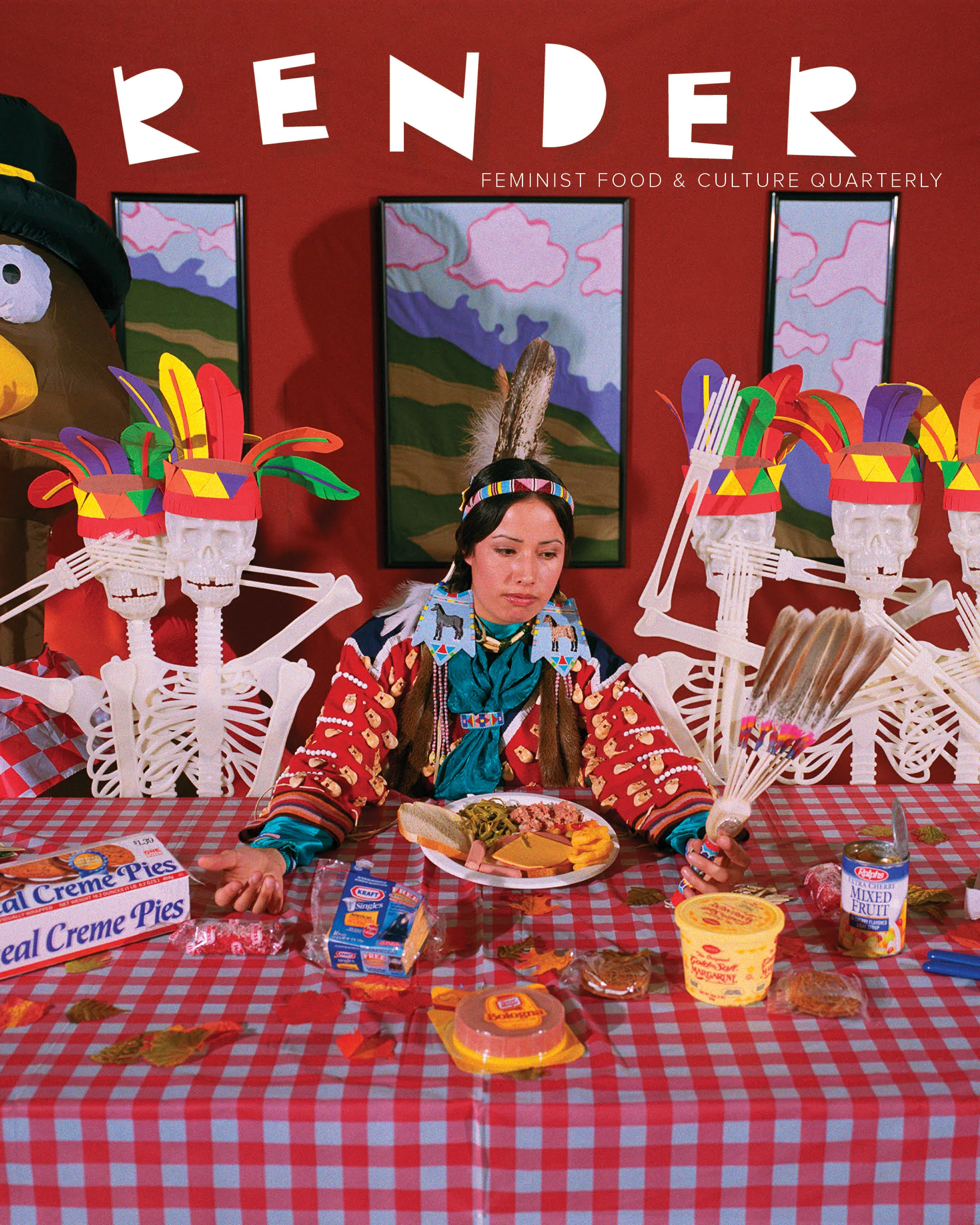

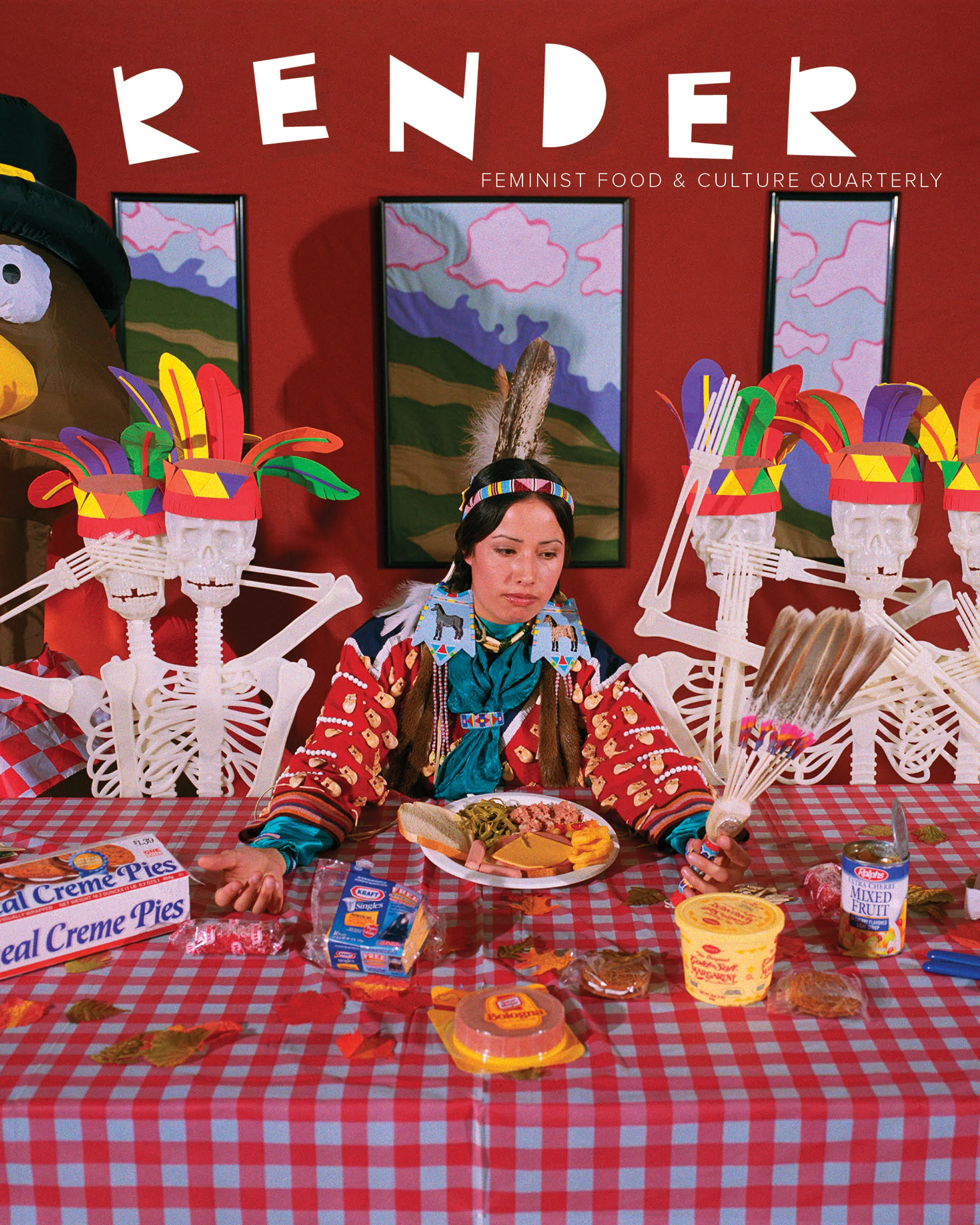

Café Rouge's Marsha McBride.

In the thump and grind of butchery, the hot red smell of blood, and the weight of fresh meat in her arms, Marsha McBride finds a deep contentment. “Growing up in the fifties, with a mother who was a disinterested cook, I often couldn’t even tell what I was eating,” she says. At eighteen she visited her older sister, who was living with her husband in Mexico City. It was here that a trip to the city’s pulsing Central de Abasto branded her memory with its energy, its bounty of sights, smells and sounds—all that fresh meat and produce made a lasting impression.

Her experience in Mexico City stayed with her, though before entering a food career, she spent seven years in social work, leading a home for runaway kids. Eventually, she says, she had the opportunity to cook for the children, which led her to take the step she had pondered years before: graduating with a culinary degree in 1983. Working in kitchens around the Bay Area, she developed a particular passion and talent for charcuterie.

In 1996, McBride opened Café Rouge, a restaurant and meat market in Berkeley. Her many accolades include winning Food & Wine’s “Best New Chef” for her work at the cafe. Chefs she has mentored have gone on to found prominent restaurants and garner their own awards, and Café Rouge continues to set the bar high for local, sustainably sourced “meaty food”.

I recently spoke with McBride about her involvement in the Butcher’s Guild, her winding road toward meat and butchery, and the future she envisions for women in professional kitchens.

Emily McIntyre: You entered culinary school wanting to become a pastry chef, and you emerged a butcher. What happened?

Marsha McBride: I always wanted to cook—after a year in school I told my parents, and my dad suggested I talk to a chef he knew at the Hilton in Oakland. That man told me that women can’t be in the kitchen because it’s too hot. I’d worked as a pantry cook one summer at St. Mary’s College, and I loved it, so I decided to apply to the Cordon Bleu in Paris, but I got sidetracked. Years later, when I decided to go to culinary school, I thought I’d focus on pastries because I have a horrible sweet tooth. Problem was, I got sick. I just couldn’t do it. At the same time, they had a Garde Manger department run by this wonderful Swiss man, and I just flourished there. I fell in love with meat.

EM: Do you have any childhood memories or influences that you think might have pushed you toward butchery?

MM: Maybe it’s in my DNA. On my father’s side of the family, we were crofters in Scotland who came to California right around the Gold Rush and became sheep farmers. My cousin, who I buy lamb from, still has a 5,000-acre ranch near Weed. Also, though my mother was a disinterested cook, my dad would make beef jerky on our roof. Here at Café Rouge we make a jerky inspired by his.

EM: Charcuterie was largely unexplored in the U.S. when you started cooking. How did it become your specialty?

MM: Well, at the time, there were a few books around, but it was pretty undiscovered territory. I was lucky that Judy [Rogers] let me just roll with it—lots of self-taught charcuterie! I also had the privilege of working with a Vietnamese immigrant whose first job, after the fall of Saigon and his immigration, was at a slaughterhouse in Texas. He was my teacher and we worked together at the Zuni Café. He still works there.

EM: Café Rouge was really one of a kind when you first opened. Now, meat markets and outstanding butchers are everywhere in the Bay Area. How do you feel about that competition?

MM: I think it raises the bar for all of us. When I started, I had an exclusive of pork, lamb, and beef from Niman Ranch! That didn’t last long. I’ve gone through a lot of butchers, and a lot of people have come to me and we’ve learned together. Taylor over at Fatted Calf started with me. I think the competition is healthy because, with the exception of beef, there are more locally-raised animals. I love the collaboration. It is good for everyone.

EM: What attracts you to meat?

MM: The smell, I think. I remember my first cooking job, under Judy Rogers at the Union Hotel in Venicia. I’d make the rounds for ingredients every morning and go to the jobber’s and the veal market. Just the smell of the fresh meat got to me. Also, I like the connection to the primal parts of our being: we really are what we eat. Ten years ago, Bobby Flay shot an episode at Café Rouge and when they wanted me to demonstrate something, I say, why don’t I do blood sausage? They said, no, that’s too gross! Well, it is! It’s not tidy—like life.

EM: What is the most prized part of your job?

MM: Cooking something. Anything.

EM: Have you ever tried vegetarianism?

MM: God, no.

EM: The stereotype of butchery is that it’s bloody, man’s work. What do you have to say about that?

MM: I think butchery is changing—Marissa and Tia from the Butcher’s Guild have a done a lot for that. I see women getting involved now: maybe it’s because there are more role models for them.

EM: On that note, what would you say to a young woman interested in butchery?

MM: I love seeing young women with that passion for butchery, and this is what I tell them: get as much experience as you can. Go ask people if you can come into their kitchens and help. In any profession there are open doors—I am not alone in that when I see someone who is passionate and interested, I want to help.

Emily McIntyre is a writer based in Portland, Oregon who explores food and beverages, and the rituals that connect us through them. When not writing, you might find her paused on her bike over the Willamette River, wondering if she can fit a clandestine reading session between princess moments with her toddler and cuppings with her husband, who is a coffee roaster. Learn more at www.emilymcintyre.com