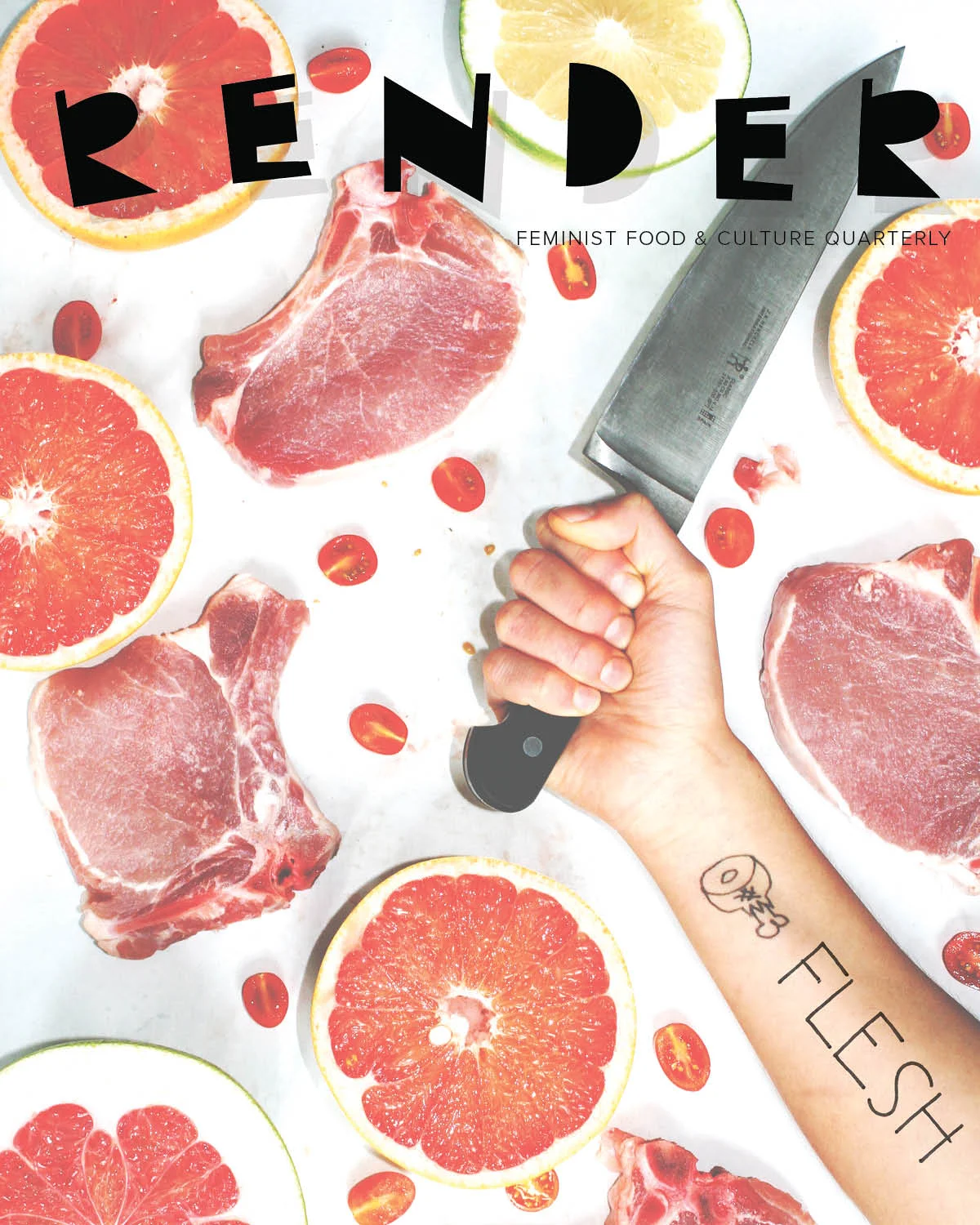

Illustration by Cate Andrews.

Welcome to The Good Curd, where each month we’ll uncover and expound upon the myriad delights of cheese. Julia Ricciardi and Brett Bankson explore cultured cream in all its glory—creamy Brillat-Savarin, salty Pecorino, funky Maroilles, crumbly paneer, freshly made Burrata, or three years-aged Gouda. The forms and characteristics of cheese are as varied and intricate as the cuisines that utilize it and the folks who make it. (Did you know that women play a key role in cheese history in the U.S.A?) This series will explore women who make the stuff, as well as reviews, pairing suggestions, and tips for selecting the best cheese for any occasion.

A couple weeks back, I sat down with Sheri LaVigne, founder and owner of Seattle’s über popular Calf & Kid cheese shop. Over some olives and red wine, we talked about her experiences entering the cheese world, her rookie mistakes as a cheese monger, and what she sees as her role in bringing products from the farm into our homes.

Brett Bankson: How did you get into cheese?

Sheri LaVigne: I’ve always been a very adventurous food person, and about two years into living in New York, I went to France for the first time. I tried everything, but of course the cheese was a mind-altering experience, so after coming back from that trip I really wanted to start to learn more about cheese. There are wonderful cheese shops around New York, but at the time there weren’t quite the boutique ones that you have now – you had like Murray’s and St. Bart’s and a couple of other places which were amazing shops, but they are huge and overwhelming and it just wasn’t my scene. That kind of put me off, but then a year or two later the Bedford Cheese Shop opened right around the corner from where I was living. To this day, it’s probably my favorite cheese shop in the US—it’s amazing. They started out like my shop now, with 200 square feet and two deli cases absolutely packed, just stuffed to the gills with cheese. So my husband and I went there and we had no idea where to start, and now I can see that the cheese mongers could read that in us. I see that all the time now—where people are bewildered and disoriented and it's just like, “All right, taste this.” So at Bedford they gave us a taste of something and we went home with three or four different cheeses. After having gone there a couple of times, and with each sample receiving some information about what I was eating and where it came from, that kind of like triggered the light bulb in my head. I started buying books about cheese and learning more about the subject.

BB: What were you doing at that point, work-wise?

SL: I never thought I would be a business owner, like ever, and at the time I was working as a bookkeeper because I had an art degree and I had worked in museums and galleries and hated that world. Office management was something that I had some experience in and it paid better than anything else I could do. The thought of working in cheese was leagues away at that point. I was just barely starting to learn about it and the people behind the counter were the real experts and I wasn’t even making that connection. So the cheese buying and learning was a part of [mine and my husband’s] lifestyle there in New York, and we would go at least once a month to drop $50 or $60 on cheese and get some wine or beer, and then instead of going out, we would stay at home and eat. We moved out here and the second year of the Seattle Cheese Festival down at Pike Place, there were tons of local cheese makers there and I had no idea there were so much interest in cheese in the area. I knew Seattle was a good food town, but I didn’t know how much cheese was happening out here, and that was in 2006 and just the beginning. When we first moved here, we were just figuring out all of our new stores and restaurants and stuff and I was like, “Oh, we need to find our cheese shop.” I was shocked when I Googled “Seattle cheese shops” and there was just The Cheese Cellar over by the EMP and that was it. I mean, Delaurenti has a great cheese counter, also Whole Foods and PCC, and those places have that middle phase, like you can have a really great experience if there’s a monger there who really cares and is knowledgeable. That one-on-one experience was what I really missed, but I still didn’t think at all that this was something that I would eventually fix. In Seattle I was working in animal welfare because that was something I had always wanted to do and I could now afford to do it, so I was making that career/dream come true. I did that for four years, and was by far the most rewarding and difficult work that I’ve done in my life. I realized after three years that I couldn’t do it long term because it was very emotionally and mentally draining, and it pays next to nothing. And actually what happened was that we went back to New York for Christmas one year and we were hanging with friends who we did cheese nights with when we were still living there, and I didn’t realize how much I missed it until we were sitting down with them again. I said, “God, we don’t have this in Seattle,” and one of my friends said, “You should just open up a cheese shop, like wouldn’t that be great? You could have this all the time.” So that’s when the seed was planted. I started looking into it and talking to cheese shop owners all over the country, really anybody who would talk to me. Cheese is one of those weird things where there isn’t any formal education system out there; it’s not like wine where you can do a sommelier program, and even culinary school doesn’t touch on cheese that much. But the breadth of knowledge that you should have to be a cheese monger is really intense, very layered and complex. I kept reading books and then I kept eating cheese and writing a cheese journal, so I was completely self taught in that sense.

BB: Did you ever have any sort of training?

SL: Yeah, it was really great timing at that point. Steve Jones down in Portland who owns Cheese Bar, he hosted a weekend seminar that was essentially “how to become a cheese monger.” There were about fifteen of us, all from different backgrounds, really a motley crew. Steve was amazing. We spent one day just doing everything on the business side—he had an accountant come in, and a lawyer too. And of course we’re eating cheese the entire time. And then the next day was cheese handling—how to cut and wrap, what imperfections and flaws to look for and how to assess them, and how to deal with distributors. And then he just let us run amok in his place. He and I kind of became pals, and I went down there for a couple of weekends just to see what it was like to work behind the counter. Jumping behind Steve’s counter, I knew maybe five cheeses in his case. It just all came very naturally to me, talking with people behind the counter. I spent the better part of the year after that traveling to different farms and dairies in Washington and Oregon, and I spent two weeks interning at Black Sheep Creamery in Chehalis because I wanted to see what it was like on a working farm—they’re about as small as you can be and still be producing cheese and making a livelihood from it. I kind of had an idea of what that life is because I grew up on a small, self-sustaining farm. My parents are educators, but my mom grew up on a farm as well, so to her it was just normal to have a farm at the house. The life of a farmer is endless, and there’s so much dedication involved, and my appreciation for people who make that their livelihood is enormous. These people work so hard to create a product and sell at farmers markets, but from a consumer’s side, you can’t always make it to every market. So my thing was that I wanted to be able to represent all these different cheese makers in one place with integrity, to really showcase their cheeses in the best way possible and take care of them. That’s kind of the service I’m able to do for them, even though I still constantly think I have the peach end of this deal because they work so damn hard.

BB: So was it that early experience on the farm that showed you how you maybe wanted to work with cheese rather than make it yourself?

SL: Oh, I’m such a city girl—even Seattle is too small for me sometimes. I’m not geared for not having all my creature comforts. So having the shop was the thing that I could do that would still play an important role in the process but be geared towards my lifestyle. I knew that I also wanted to be filling the education role, because people don’t understand what cheese is or where it comes from, kind of like where wine was 30 years ago. It’s definitely getting there, like people are starting to understand that cheese is a value-added product, that you’re paying for a whole entire process that results in this complex product in your hand.

BB: You’re paying for time—it’s like edible time!

SL: Yeah, exactly. And that was another the light bulb moment for me, realizing that cheese is the result of an entire culture (literally), an entire process through time, and cheese is a little piece of history. I do cheese tasting classes, and I’m glad people do latch onto those and want to learn. At the counter, we do as much as we can, but you can only do so much in that setting. And that’s why the cheese bar that we’re opening up is such a big deal, because it’s this space where it’s all service oriented—cheese flights, cheesy foods, places for cheese classes.

BB: What was the most difficult or daunting part of the business-building process for you? You said you just cold-called dairies around the nation and read books, but I know that that would have been really intimidating for me had I been in your shoes. And then just always wondering if I was doing enough or doing it right—how did you continue?

SL: The education part I actually felt really good about, because I didn’t put myself on a timeline. Putting myself out there was not daunting at all; what was the most terrifying part was securing funding. This was when everything was crashing, so no one was giving out SBA [small business administration] loans and I even cashed in some retirement funds. I ended up posting on Twitter, and within two weeks I had three investors.

BB: Were these people in the cheese community, or just über wealthy?

SL: No, not even. One was a gal that I met at the weekend seminar that Steve did, so she was the first one that I approached. The other two were just completely random and had been following my blog and had money they wanted to put into the community. It was like 10k a piece, so it wasn’t an angel investor or anything. That took a lot of time because creating the legal documents for that was its own thing entirely. I think that I had as much preparation as I possibly could have had, and even then that first year was full of rookie mistakes.

BB: Like, what sort of mistakes?

SL: Purchasing, quantity-wise: I made the mistake of buying stuff from people without asking the wholesale prices first. I would get these wheels of cheese and would have had to sell them at $50/lb., but I couldn’t do that so I would have to cut my prices way down. Also figuring out what people really wanted; I had my own idea of an approachable cheese case.

BB: Which was?

SL: A smattering of everything, and of course showcasing the local stuff. But when I think back, I think of the cheese I opened with as very pedestrian. I was much more thrifty. The biggest change happened from year one to year two, when I realized that people want what I want to sell, which is stuff with big flavor, you know—stinky washed rind. That’s something that you just can’t get anywhere in town, and you never want to buy a washed rind if it's been cut and wrapped because the minute that sits in plastic for even a day it gets rancid; and most places know that so they won't sell it. When you look at the other shops here in [Melrose Market], you know it’s a high-end group of stores, so it’s very rare that people balk at our prices. I realized that and I started bringing in stuff that was retailing for $40/lb., very tentatively, and people were like, “Fine!”

BB: Did you branch out more international after that first year? I looked at the case and it seemed like you had a pretty good Italy, France, and Netherlands representation.

SL: Well, it changes based on the season mostly. Like right now, we have the least amount of domestic cheese available because everyone is just now starting lambing and kidding and starting to milk. Then in April, May, and June, the domestic stuff that’s fresh will be coming in, so I always take the winter as an opportunity to try other imports. In March I do a regional cheese swap with a gal in Tennessee, and that’s really fun because there are a lot of really awesome cheese makers in the South and Southwest. So we just trade each other a box of the stuff neither of us can get from other regions. I’m looking into doing that with someone else, maybe East Coast. In the shop, everything is constantly rotating so that it stays interesting, and there are always new cheese makers popping up locally, so there’s new stuff to try.

BB: You said you like bold, funky flavors, so do you carry washed rinds over other cheeses or anything like that?

SL: No, I’d say the only thing that we try to keep is a very balanced mix. Every cheese that goes in the case is a very deliberate decision, so that’s why in the spring and summer time I’ll kick out some of the imports to make room for the domestics. There are staples that I personally have to have, like Neal’s Yard Dairy—I couldn’t have a shop without having their cheeses. I definitely probably veer towards France and Switzerland when it comes to imports.

BB: Like alpine cheeses?

SL: I definitely love alpine cheeses and there are a lot of great ones available, but overall, I take everything French. That’s where I fell in love with cheese, so I’m impartial, but one of my distributors is a Corsican fellow too. He’s a smaller importer, but he brings in this unbelievable catalog of stuff, and many of the cheeses he brings in are literally unavailable anywhere else in the country because he grew up with the nephew of the cheese maker. Since he brings in such incredible specialty items, I end up being able to carry stuff that you don’t get anywhere else. There’s even a good handful of cheeses that I love but don’t carry because you can get them at any QFC, so there’s no need for me to do it. Like with Beecher’s, they’re just down the street and they’re everywhere, so even though I love Flagship, I don’t need to carry it.

BB: Have you ever had casu marzu?

SL: *laughs* No. And I never will. That shit freaks me out. I think Andrew Zimmern was doing one of his shows in Italy and he was tried casu marzu, but he didn’t eat the maggots. He just ate a bit of the cheese, and even he was like, “That’s the most wretched thing I’ve ever tasted.” So if even he says that, I’m not going anywhere near it. Of course, not all cheese is good, like not all wine is good. There’s this other stuff, do you know gjetost?

BB: Yeah, it’s been on my try list for like eight years, definitely.

SL: It’s so awful.

BB: Would it be different if you had grown up with it?

SL: I think a lot of people liken it to like marmite in the sense of it you had grown up with it you would like it. I think there are certain things that people can’t do, like there are a lot of goat cheeses that I don’t like because of that super billy-goat flavor.

BB: Fresh or aged?

SL: Usually soft ripened, like bûcheron. I really don’t like that flavor; that super grassy, super tangy flavor that feels like a goat is running through your mouth. It’s interesting because that’s a very strong characteristic of goat cheese, so a lot of people have come to think that that’s what goat cheese has to taste like. One of my favorite things to do is to dispel that rumor and show people that all goat cheese doesn’t taste like that. There are lots of goat cheeses that are very milky and have a lot of great nuances.

BB: Have you had any experiences where being a woman in the industry has been difficult? I ask that because it's been interesting talking to women cheese makers and having most of them tell me that everyone is very supportive of their work, regardless of gender, and so it seems like it’s a pretty small, intimate industry.

SL: In the cheese world, no, that hasn’t been a problem, although it’s still predominantly a male-led industry.

BB: Luckily we don’t live in France.

SL: Yeah, that’s exactly what I was going to say, that in a lot of old world European countries you don’t see female cheese mongers or cheese makers hardly at all, and I imagine they struggle with it a lot. Here, it’s such a small industry. As far as the cheese world, I’ve never felt any kind of discrimination, but as a business owner, I totally have. Being a female business owner and experiencing the personal politics that exist has been difficult, especially because I’m on the cusp of the restaurant industry but I’m not really in it. The food industry can definitely get gnarly with gender. I’ve felt it a lot with the bro club and getting pushed out because I’m not a part of that; I dealt with it a lot when I was doing construction, and it was just having to stand up for myself a lot more than I feel other people probably had to. Luckily for me, when I was doing office management and book keeping, that was for a contracting company in NYC, so if there’s one thing that doesn’t even faze me at all, it’s contractors and construction workers because I had to manage that for a while.

BB: What has it been like getting involved with the Seattle food industry, like wine and product ties? What’s it been like making connections with other restaurants and markets?

SL: In terms of just building relationships and getting to meet people, it’s wonderful. I’ve met lots of wine reps because I’m next door to Bar Ferd’nand, so that’s great, and that’s been really helpful for opening the cheese bar because I already know all of them. It’s the same with meeting a lot of vendors that work directly with the stores here, like vegetable suppliers. I wouldn’t have that benefit if I were a standalone shop, so it’s been very advantageous to be here [in Melrose Market]. In general, getting to know people here has been really awesome and like I said, I don’t think I would have had all of that, such a close-knit thing, had I been a standalone shop - I thank my lucky stars all the time for finding this space. Probably the single best piece of advice I got from anyone was from my friend Jason who’s owned a construction company for about 20 years. He told me, "Just don’t rush. If you try to force something to happen, you’re going to be backpedaling from it forever and you’re never gonna make it up.” And that was one of the reasons that I took my time at the beginning of my process and didn’t give myself such a strict timeline.

BB: Off the top of your head, what’s your favorite cheese, or what cheese just comes to your mind as something you’re enjoying now?

SL: I mean, my old standbys are always a plus, and I also like Montgomery’s cheddar; those are my desert island cheeses. Rheba from Tieton Creamery has been way at the top of my list this year. It’s a sheep and goat mix and it’s washed in a little bit of beer I think, and it’s not stinky at all for a washed rind. And actually Briar Rose Creamery, their Lorelei—I love that cheese but it’s not available right now. And there’s a newcomer, a place called Domina Dairy down in Chehalis that has this one-year Gouda, Neuwaukum Hill. It’s available spring and summer and it’s unbelievable. It’s so good.

Calf & Kid is located at 1531 Melrose Avenue in Seattle, and is open 11 AM – 7 PM Monday thru Sunday.