I was first inspired to revise tradition by the garnish on a classic burger and fries I was eating. The meal itself was unmemorable, but the three, small pickled strawberries nestled in a lettuce leaf alongside the hulking patty were a revelatory marriage of sweet and savory. I had dabbled in pickling—my Pennsylvania Dutch grandmother made nearly a dozen kinds of pickles a year, with large Tupperware platters pulled out for every holiday smorgasbord.

But, she had never pickled strawberries.

I took a recipe of hers for a bread and butter pickle and decided to swap basil for the dill and honey for the white sugar. I simmered a brine on the stove top and chose only unblemished berries and herb leaves for the jar. I poured the sharp smelling brine into the jars of strawberries and herbs and allowed this mixture to sit in the fridge for a few days. The result was unlike anything I had ever made before—acidic and fruity, equally at home atop sharp cheddar or cheesecake. Yet, the technique was purely traditional.

I, like many others, grew interested in home preserving and gardening and “traditionally” prepared foods not long after the turn of the new millennium. The political climate, environmental concerns, and the first rumblings of the recession motivated many folks to look to the past for something simpler, to try to connect with our heritage or forge a life less dependent on large corporations. Thus, the new “American Artisanal Movement” was born.

Interested in this burgeoning food movement, I interviewed more than fifty commercial food artisans for my recently published book Small Batch: Pickles, Cheese, Chocolate, Spirits and the Return of Artisanal Food asking them how they would define the term artisanal and what inspired their entry into this industry. What I found was that while people became interested in small batch foods for personal, cultural, and environmental reasons, they also had a strong business grounding. And, what made this new movement toward traditional foods and methods so different from previous countercultural and back-to-the-land movements was these entrepreneurs’ commitment to working within the existing commercial system, even if it was on slightly altered terms. While quality and a dedication to a handmade ethos were important to them, as well as sustainable sourcing in many instances, the business end of their trade was about identifying a product that fit these criteria but was simultaneously unique enough to stand out while also being familiar enough to consumers to get them to purchase their product.

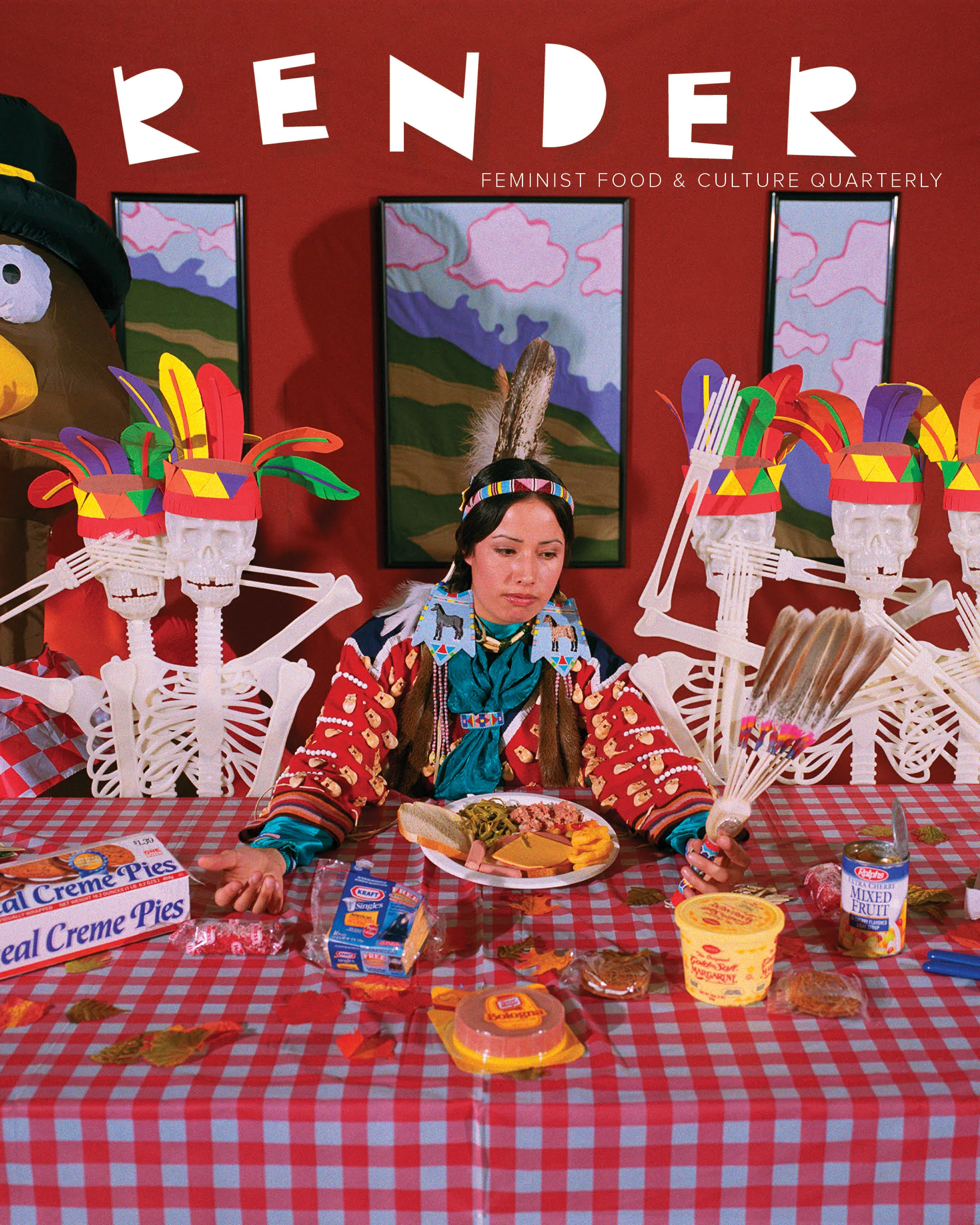

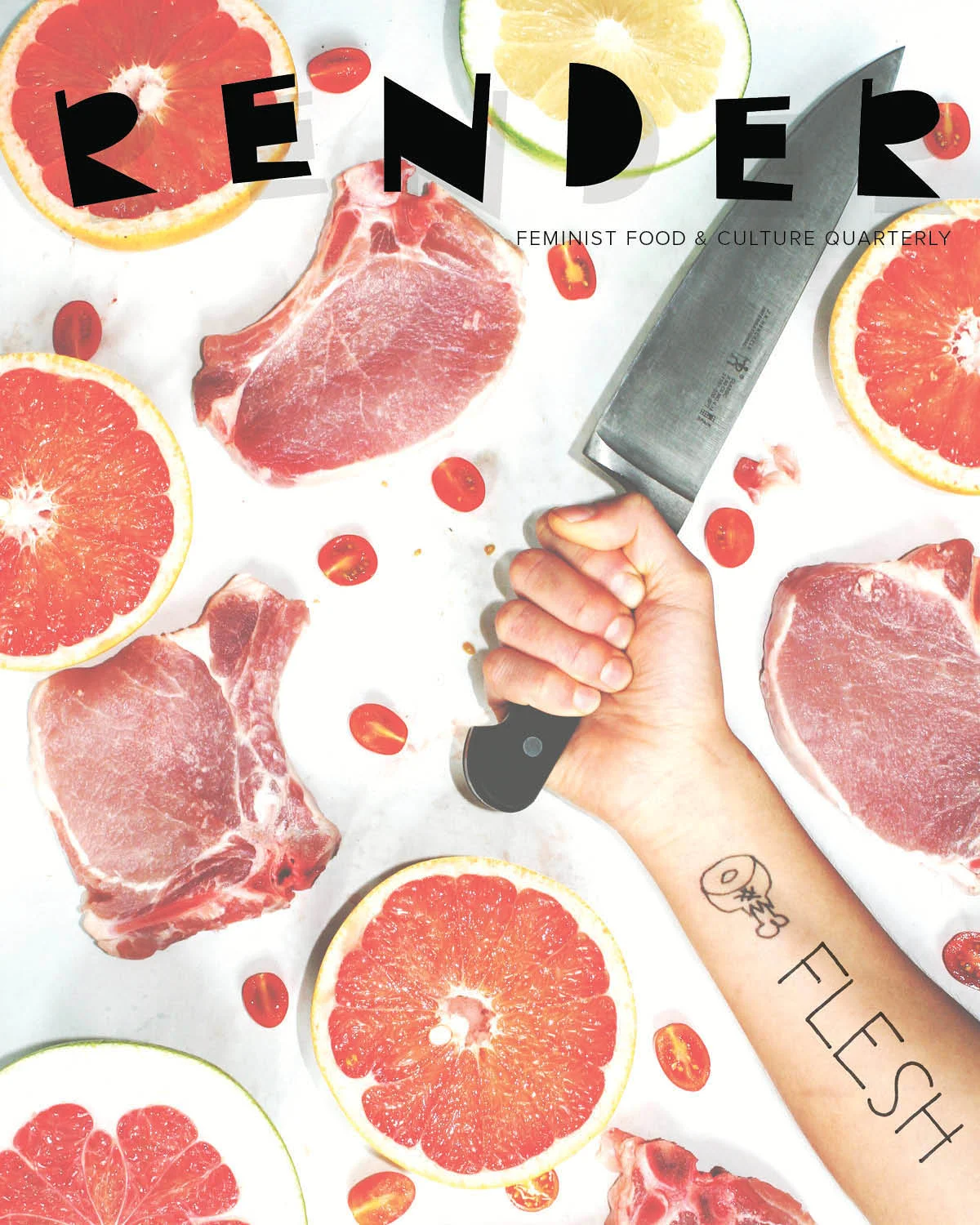

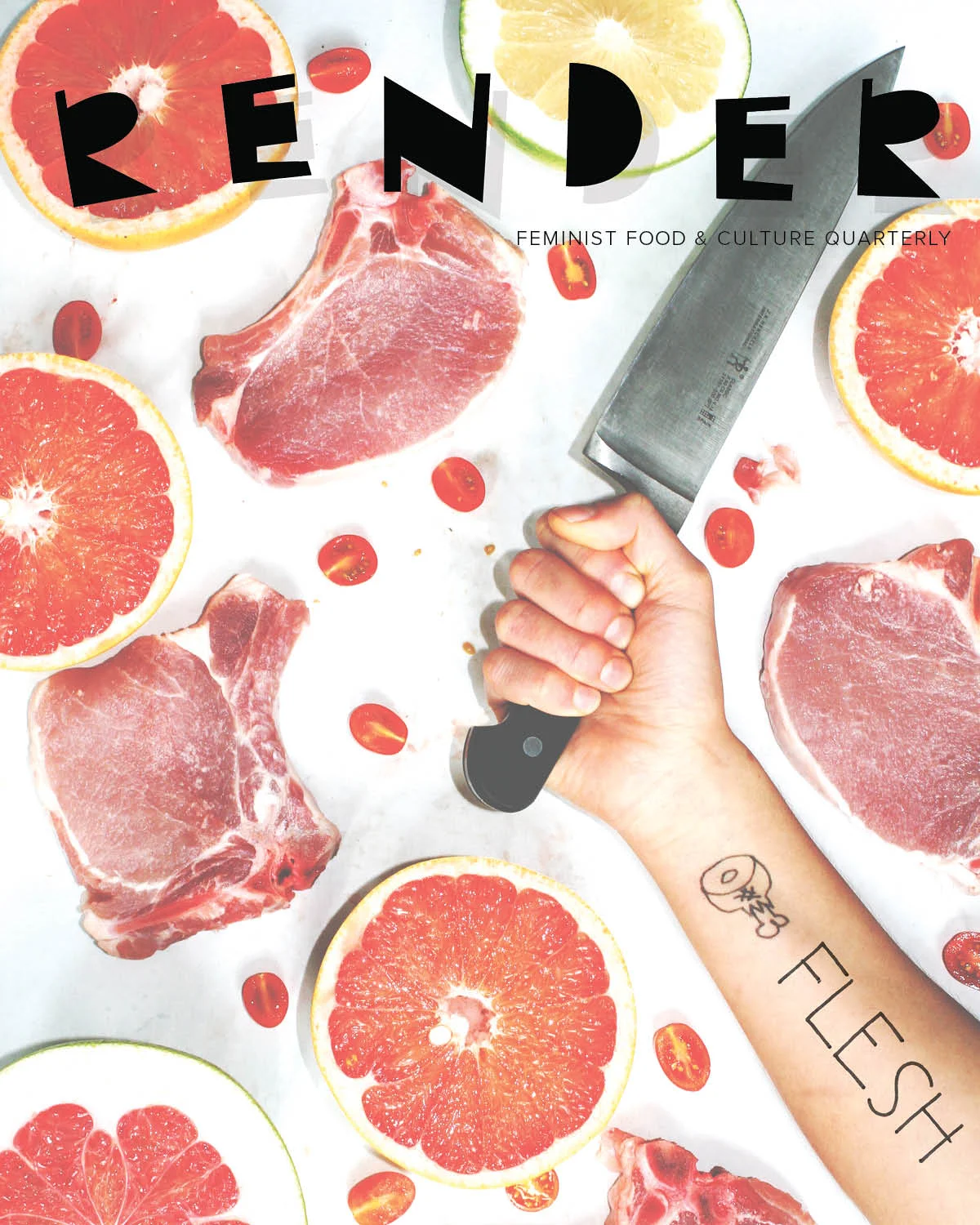

Images via Suzanne Cope

This concept of “traditional” artisanal food is different in other cultures, such as France, Italy, and Spain, where there are much older and established artisanal food industries than the United States. In these countries, artisanal products are even carefully regulated to ensure their purity to taste and technique. The absence of regulations and strict definitions is what makes the American artisanal food culture unique: most entrepreneurs, while they nod to the past to package and sell their products, are very much making products for the modern-day consumer. Dark chocolate bars, for example, are perhaps somewhat similar to the bitter unsweetened cacao-based food and drink of a millennium earlier, but the shiny chocolate bar is a distinctly contemporary creation. And, while cheesemaking methods have not changed too much for generations, the flavor combinations – rubbing coffee on the rinds to add earthiness or infusing the milk with lavender for a floral and aromatic component – is distinctly contemporary. These new takes on “traditional food” are a uniquely American creation, one that helps new food artisans distinguish themselves and be competitive in a growing specialty niche market.

Thus, tradition does play an important role in the new artisanal food revolution, but so does innovation. Even if many of the artisanal products today aren’t exact replicas of recipes from the past in terms of ingredients, technique, or flavor, the impetus to base these news foods on knowledge from the past is still a valid one. Traditions are fluid—we make them up anew constantly. While I may follow some of my grandmother’s recipes to the letter, there is both intuitive and time-honed knowledge that she has that cannot be written down in a recipe and that I cannot replicate. That aspect of her technique will be forever lost once she is no longer preserving. Yet, she has also given me the tools to move forward with (re)creating my own traditions. I couldn’t have made my own pickled strawberries if I didn’t have the memory of her pickles and the document of her recipes to base it upon. Will I teach my young son to make pickles using his great grandmother’s recipe? Certainly. And, I will also teach him my own. But I hope that I am perpetuating and creating traditions for my young son to be inspired by – and not merely imitate – when he is old enough to stand at the stove and start pickling.

Sweet Pickled Strawberries

*fills about a pint jar of strawberries

In a sauce pan, over medium heat: heat 1 cup vinegar, 3/4–1 cup sweetener, such as sugar, honey, or agave (depending on sweetness of berries, sweetener used, and personal taste) and 2 tablespoons of salt. Perhaps add a teaspoon or two of vanilla extract if you prefer, or half of a vanilla pod. Heat until the sweetener and salt are dissolved and the liquid reaches a high simmer, stirring frequently. As soon as it reaches this stage it is ready to use, although you may keep it at a simmer until the next step is ready.

Meanwhile, clean and de-stem enough small, ripe, blemish-free berries to fill a clean pint jar. Layer in a few clean and unbruised mint or basil leaves.

Pour the hot liquid over the strawberries. Once at room temperature, store in the fridge. Let berries sit 12–24 hours or more before serving.

Dr. Suzanne Cope is the author of Small Batch, an academic, and a writer.

Interested in reading more about food traditions and their reinvention? Subscribe below to receive our second issue, ROOTS, out in December.