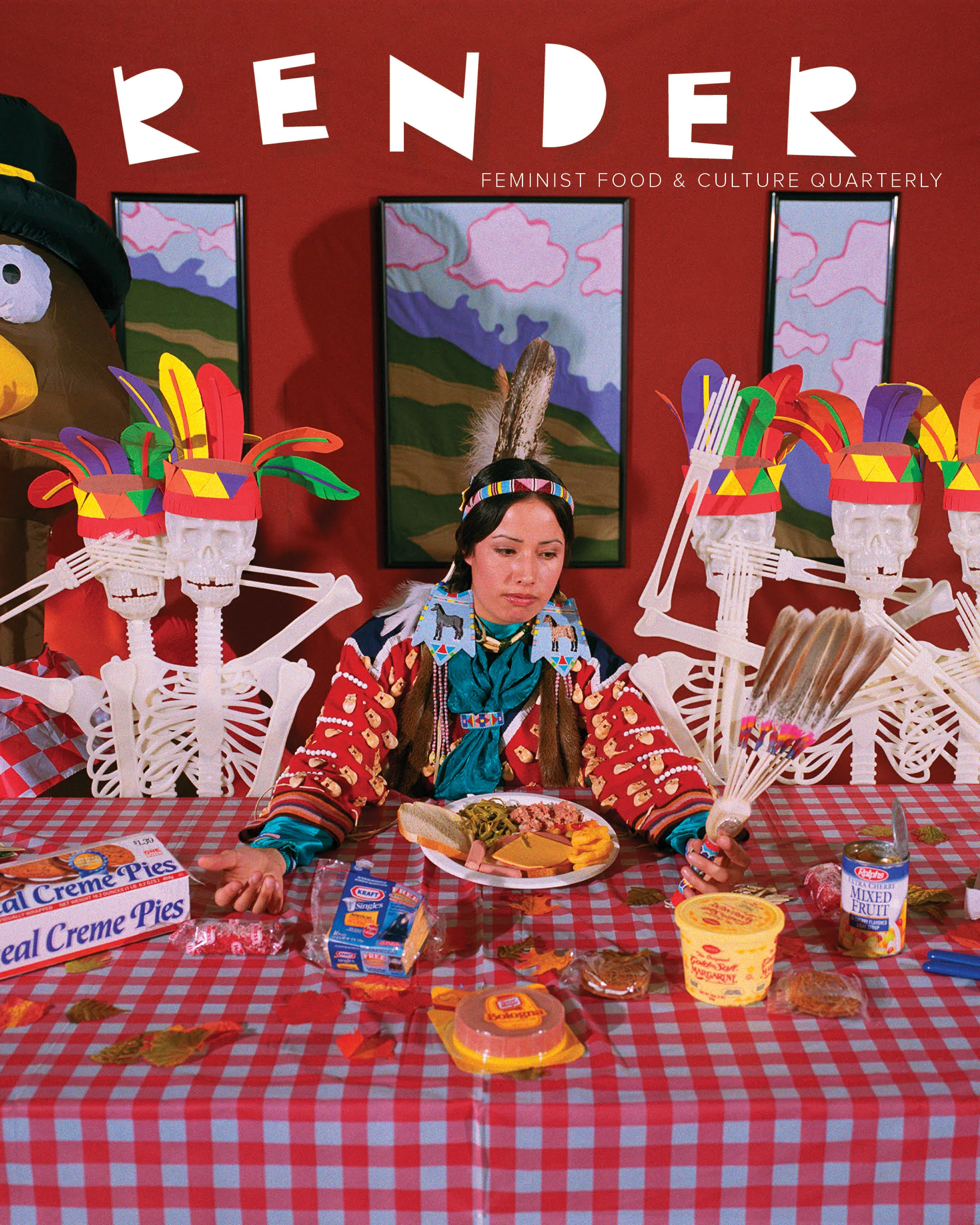

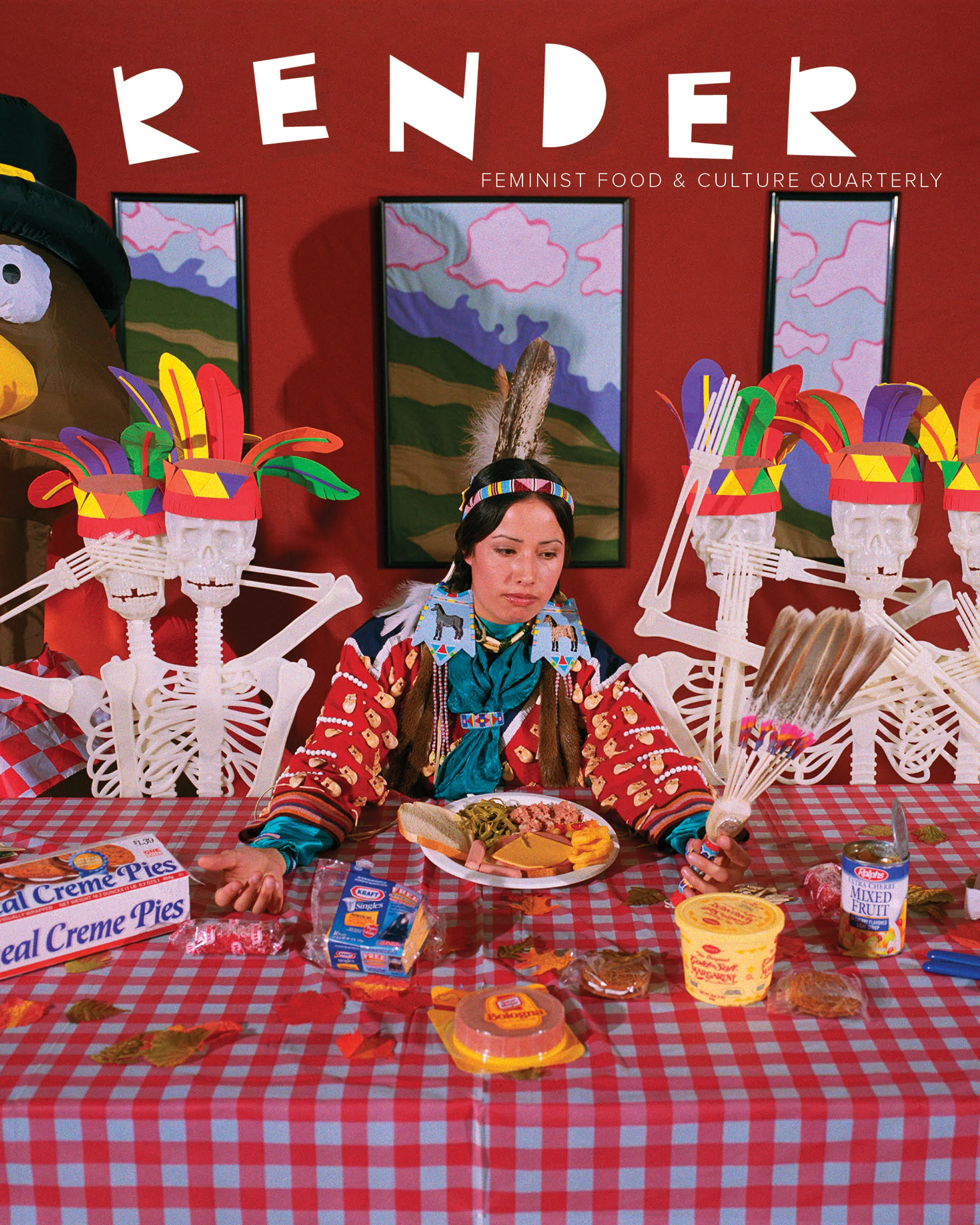

Students in the course dining at Das Ethiopian. Photos courtesy of Johanna Mendelson Forman.

In each installment of Breaking Bread, Phylisa Wisdom will discuss gastrodiplomacy—using the history of different foods, and eating and cooking those foods, to foster understanding and cooperation between cultures. Think of it as breaking bread to break down barriers. We’ll explore who gastrodiplomats are and what they’re doing – or cooking – to engage in dialogue with, or about, other cultures and countries. The column will feature interviews with sassy changemakers, recipes from chefs involved in gastrodimplocatic efforts, and analysis of effective efforts (and sometimes wretched failures) from all over the world. We’re unapologetically in favor of talking politics at the dinner table.

Gastrodiplomacy, or culinary diplomacy, is the interesting new trend on the diplomacy block. Ideas about the potential influence of food and dining have penetrated what is often dense diplomacy discourse among academics and researchers. Professor Johanna Mendelson Forman, with the help of food researcher and writer Sam Chapple-Sokol, developed the American University course “Conflict Cuisines: An Introduction to War and Peace through Washington’s Ethnic Restaurant Scene.” The course, which ran last year out of the School of International Service (SIS), explored the shifting nature of modern warfare and conflict while analyzing the effect of conflict on an exceedingly global culinary world. “This class was about teaching students about diaspora cuisines—how they became a form of communication and memory,” Mendelson Forman told me over email.

Mendelson Forman is interested in working with diplomacy students to help them think critically about the role that food plays in international relations, particularly with regard to war. “What I was interested in doing was exploring how food can serve as a tool of ‘soft power’, how immigrants can be culinary diplomats in reverse, and how these different cuisines reflect memories that are often all that is left when people can no longer go home.” Sam Chappel-Sokol added that the aim of the course was “on a basic level, to educate students interested in international studies about recent conflicts that are often misunderstood and under-taught in the post-9/11 world, those that took place during the Cold War.” Additionally, he told me, “this course clearly showed that food has a serious place in an interdisciplinary ‘liberal arts’ field, and that approaching internecine strife and global proxy wars through food studies is no less valuable than doing so through literature, art, or even geography.”

According to Mendelson Forman, in Washington, D.C. “you can always tell where in the world there is a conflict by the new ethnic restaurants that open." This presents a unique opportunity for American University students – potentially the public diplomats of tomorrow – to engage with the local community around the restaurants and cooking that help maintain links to former homelands, often those that international relations or public diplomacy students read about in scholarly journals and textbooks.

The benefit to American University and its students is clear, but in what way – if any – is this beneficial to the purveyors of the restaurants the class visits? This course facilitates a dialogue between two groups – students and diaspora populations – that likely would not have occurred organically. Simply eating in a restaurant, like Das Ethiopian in Georgetown (one of the restaurants the class visited), is not enough to engage with a community, family, or country in any meaningful way, of course. To assume that one learns about a culture or conflict by osmosis through food alone, especially when the goal is to learn about nuances of diaspora, war or other conflict, would be entirely remiss. The essential piece is the engagement with people like Sileshi Alifom, the owner of Das Ethiopian, who spoke to students about how his family uses the food of their homeland to stay connected to a place that feels like home, but can’t be because of a conflict.

As it stands, the forward movement that results from this class is on a micro-level; it is not effecting international policy or relations in any major way. Still, according to Mendelson Forman, “this new take on the town and gown divide may actually help bridge a gap that often exists in the United States: distrust of newcomers, or more significantly, misunderstandings about different cultural norms.” However, Chapple-Sokol acknowledged that the course is probably preaching to the choir, saying, “I'm not sure I'd say that the course itself aimed to combat xenophobia, because its audience wasn't (we assume) particularly xenophobic to start.” I asked about how Mendelson Forman and Chapple-Sokol aimed to ensure that issues of social justice were discussed and fleshed out with students. “When talking about food security, social justice is never far behind, and many of our discussions about issues of agribusiness, food distribution, and food supply in both war and peace were deeply imbued with issues of gender inequality, structural violence, and the ironies associated with farming and hunger,” Chapple-Sokol said. Including restaurant owners and staff in these conversations does ensure that the discourse is not defined only by the opinions and analysis of those with a formal higher education in the United States, who potentially have never been to the country in question.

Understanding food, cuisine, and post-war food consequences could tangibly impact society. In a recent study in Public Diplomacy Magazine, over half of the 140 people surveyed said that they felt more positive about a country after eating at a restaurant that serves its food. For gastrodiplomacy to be effective and socially just, it pays to think about the half that didn’t feel more positive about a country after eating its food. The simple act of consuming does not, in itself, lead us to draw any meaningful conclusions about a country or be more respectful of its expats, of course. But, by intentionally engaging with the food culture, cuisine, and politics of diaspora populations, there is potential to forge stronger, more informed bonds and potentially prevent some of the devastating consequences of war.

PHYLISA WISDOM HAS AN MA IN PUBLIC POLICY FROM KING’S COLLEGE LONDON. ORIGINALLY FROM SAN DIEGO, SHE’S NOW LIVING IN MELBOURNE, AUSTRALIA LEARNING FIRSTHAND WHY IT’S THE COFFEE CAPITAL OF THE WORLD. FOLLOW HER ON TWITTER AT @PHYLISAJOY.