Photo from USDAGOV

When the Modern Farmer article “Painting the Farm Red: The Chicken-Slaughtering Pinup Girls of Marion Acres” appeared in my inbox, I took once glance, deemed it inconsequential, and deleted it. Then it started popping up all over my Facebook feed, and the images of twenty– and thirty-something women in bandanas and red lipstick leering at chickens stuffed into slaughtering cones was too difficult to ignore, so I clicked. When my friend Lora asked me for my feminist analysis, I balked, “I have no real feminist analysis. I just think this is profoundly dumb.”

Despite my initial reaction, the complex implications of that story (if you can call it that) have stuck with me and left me wondering what the piece might say about the societal fetishization of women and meat, agrarian labor, and rural culture. Turns out, I have a feminist analysis after all.

The photo spread, which by all appearances is little more than a native advertising spot, depicts an annual event at Marion Acres, an “artisan poultry” farm outside of Portland, Oregon. For the event, women are invited to the farm to dress up in vintage “pin-up” style attire and make-up and then butcher chickens for a day. But it’s not only the fashion that evokes an antiquated style—the text of the article itself is rife with phrases that seem fitting for a “good time was had by all” ‘50s gossip rag, with its belittling quips like, “all the women go home appreciating where our food comes from.” Despite being thinly-veiled promotional material, there’s still a lot to unpack in the article’s enunciations, whether they were intended or not.

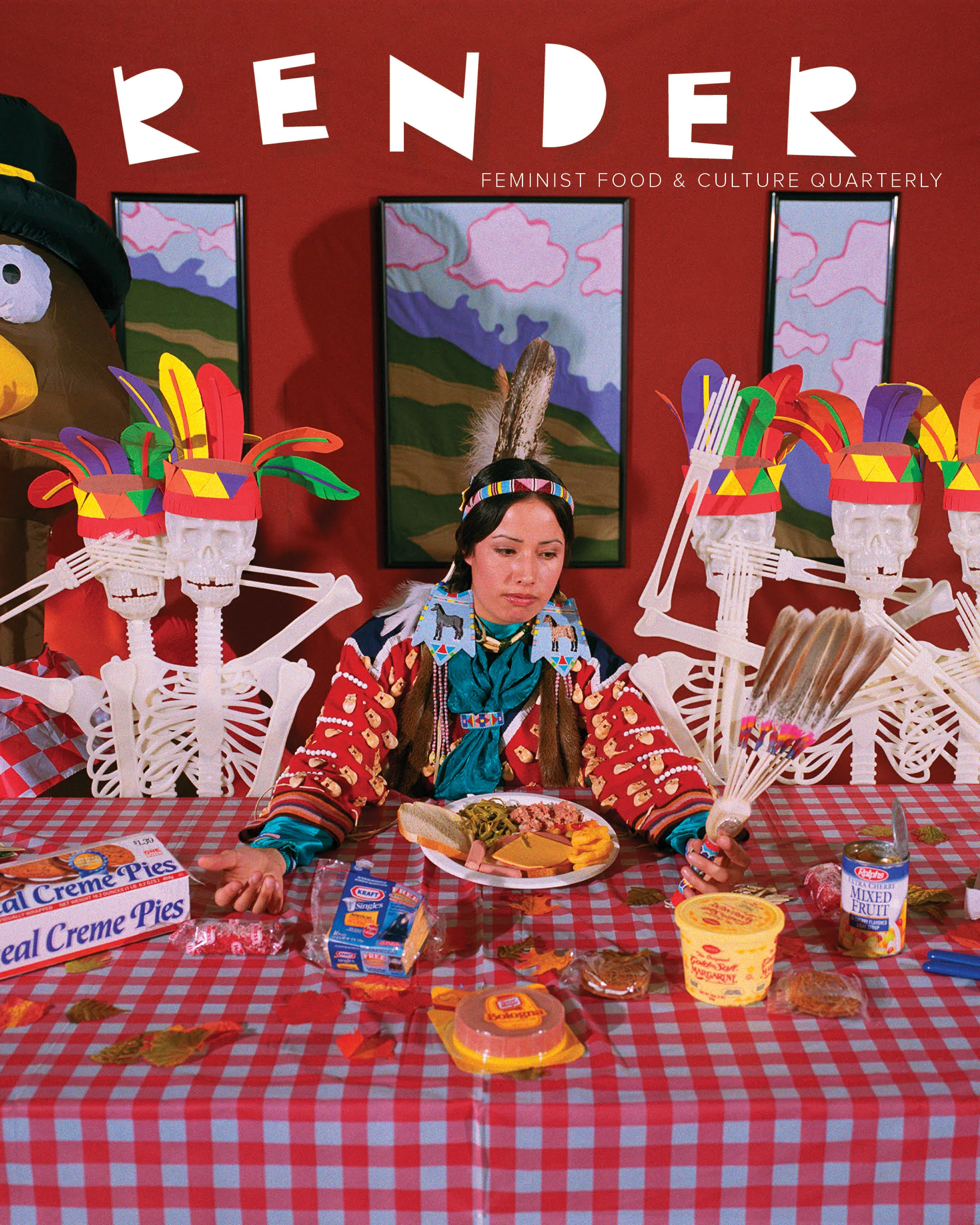

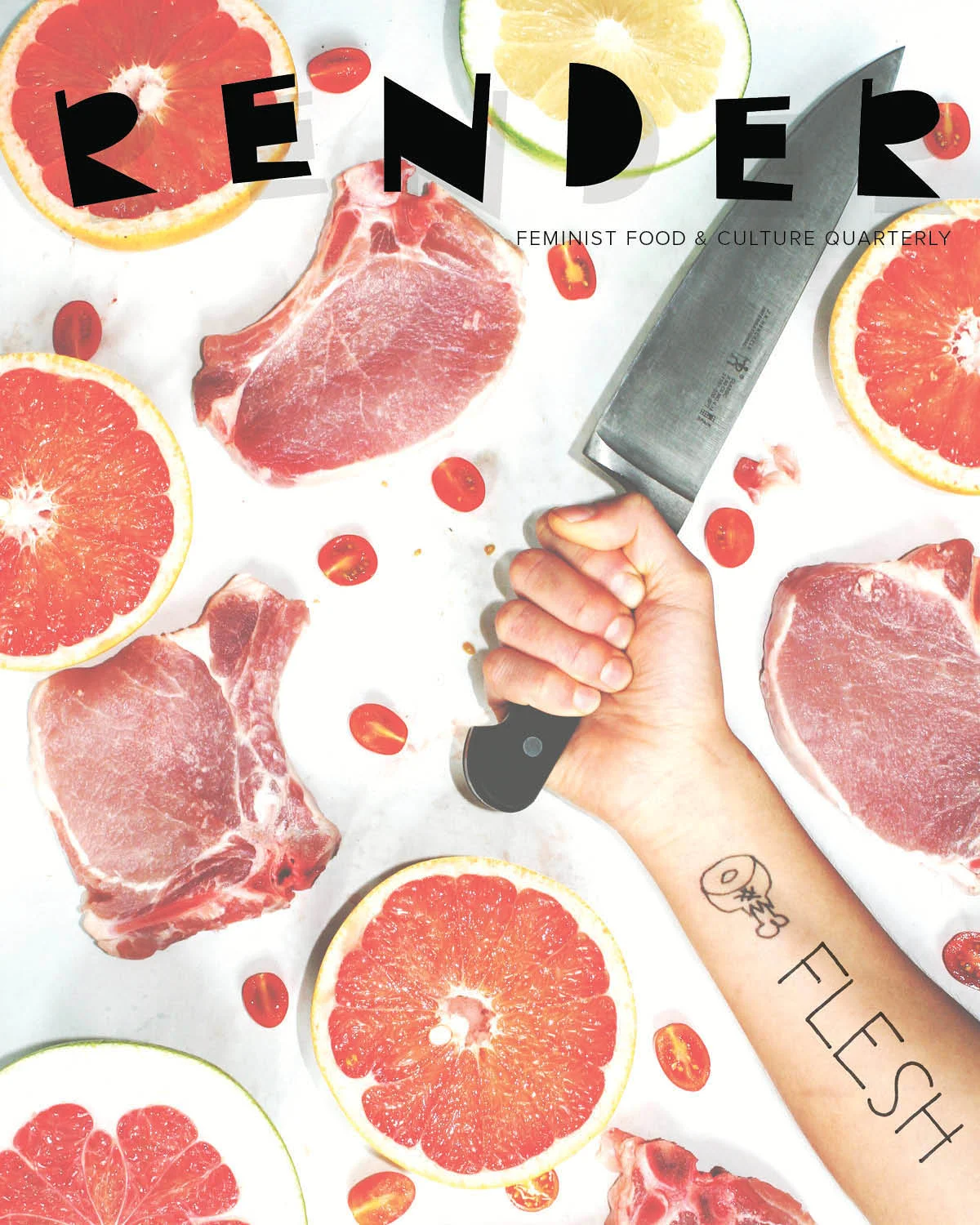

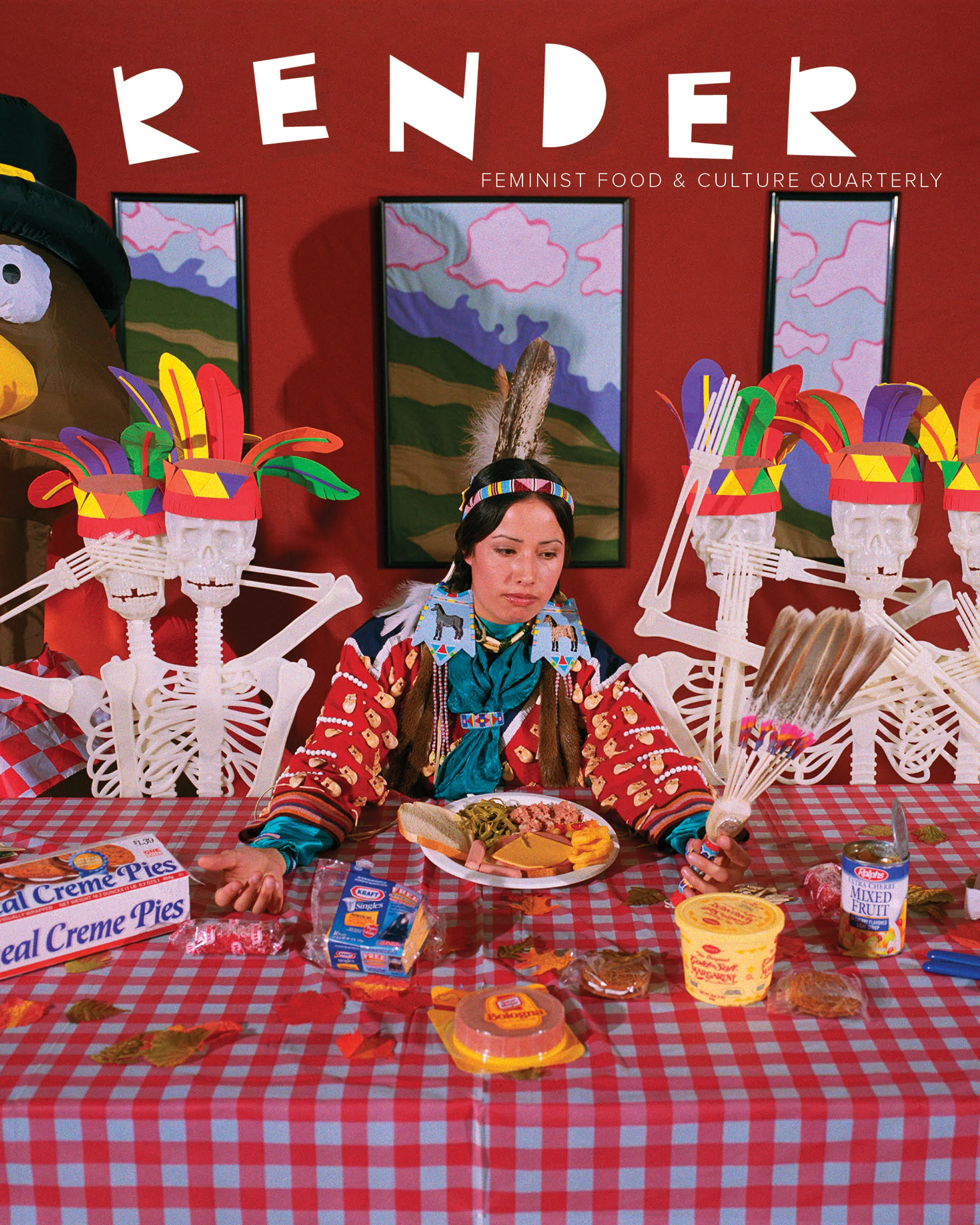

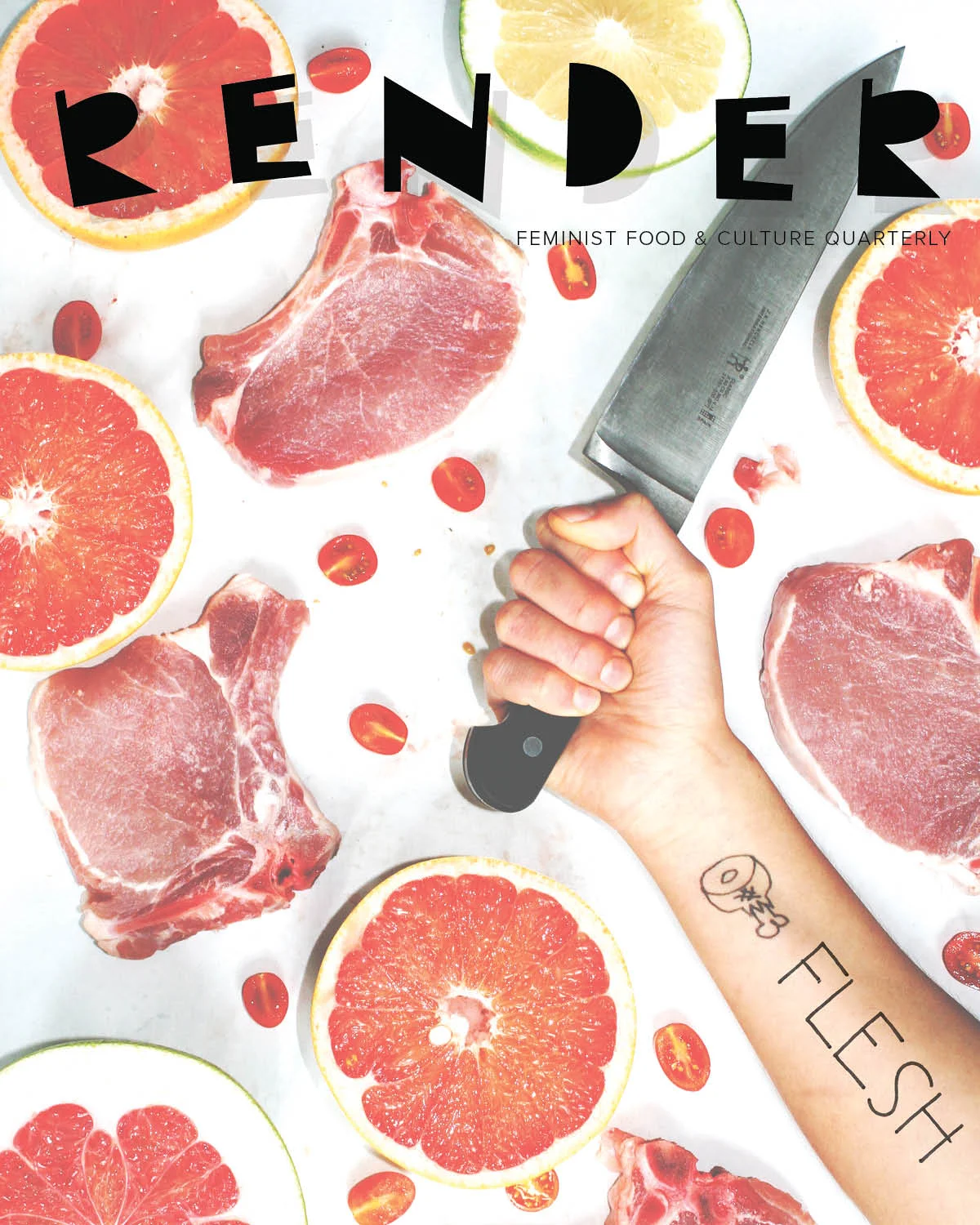

What jumps out immediately is the strange entanglement between the chickens and the women who slaughter them. Underneath an image of women in bandanas, victory curls, and immaculate floral aprons who are cradling white hens, the copy reads, “Once a year, friends and family of Marion Acres gather up all the girls to do what we like to call our ‘Ladies’ Chicken Harvest.” It’s strikingly unclear if they’re referring to the chickens or the women. What “girls” are they gathering up? And who, in fact, is being harvested?

It doesn’t stop at mere confusion between the actor and the acted upon, but goes on, “All the ladies get dressed in vintage clothes, pin-up inspired hair, and of course, red lipstick to do our butchering. We couldn’t think of a better way to knock em’ dead!” There’s a strange double objectification there, an othering of both women and poultry that feels unsettling. Though the author of the piece is female, she assumes the voice and gaze of one of the male Marion Acres farmers depicted in the photos, in a collective “we,” who casually observes the polka dot dress-clad women and their soon-to-be fresh meat.

This alignment of women and meat as object is not a new phenomenon. Its history and import is outlined and analyzed in detail in Carol J. Adams classic feminist-vegetarian critique The Sexual Politics of Meat. In the book, Adams explores the connection between viewing animals solely for carnivorous desires and women for merely carnal ones. As a long-time vegetarian-turned-meat eater, some of Adams’ radical vegetarianism is too extreme for me, but on a basic level, I understand and appreciate her core points, which professor of animal and environmental philosophy Matthew R. Colarco describes in the preface to the twentieth anniversary edition as, calling “explicit attention to the carnivorism that lies at the heart of classical notions of subjectivity, especially male subjectivity. Just consider how many times you’ve heard women describe feeling like a “piece of meat” or seen the Hooters and barbecue joint signs with suggestive metaphors the likes of “sweet racks and tender butts.” It doesn’t take much to see how our society often applies a carnivorous gaze to women’s bodies.

Aside from the groan-inducing pun of “knock em’ dead,” the exclamation is troubling not just for how it relates the women’s appearances with the death of the chickens, but for the way it makes light of the realities and hard labor of meat processing, whether small-scale and sustainable or industrial. Sonya Holmes, a second-generation poultry farmer in Harnett County, North Carolina, who does advocacy work with almost 200 other farmers in the state, spoke to me about her experience with slaughter saying, “No one that I know takes the slaughter of the animals they care for lightly. They raise the poultry (or any other animal) with the utmost care and concern. They also understand that the slaughter is necessary to provide the needed protein for public consumption.” Many of the dissenting comments on the Modern Farmer piece are reactions to the gruesomeness of slaughter in general.

My objections to the piece do not lie with the gruesomeness of slaughter itself— the fact of death implicit in meat consumption is something I see as a fact that every meat eater reconciles in his or her own way. What concerns me is the way the performance of slaughter by the women at Marion Acres manifests as an erasure of the realities of the profession, contributing to the demeaning of women who make their livelihood in agriculture. This is not only an erasure of true agrarian labor, work that is so often romanticized, idealized, and packaged for consumption these days, but the article’s quips like, “Most of the women have no idea what to expect,” and “regular farmhands make it seem effortless,” contribute to the struggle for credibility that women in farming professions face. According to the most recent USDA Census of Agriculture, 46 percent of farm operators in the United States are female, but despite this nearly equal distribution between the genders, the field is still perceived as male-dominated and controlled. Image crafting like that out of Marion Acres depicts women as incompetent, disempowered, and dependent on the help of men in the agricultural arena.

Similarly, these whitewashed and glossy images also obscure the racial diversity and financial realities of the meat industry. According the 2005 Human Rights Watch Report, “Blood, Sweat, and Fear: Worker’s Rights in U.S. Meat and Poultry Plants,” the majority of workers in slaughter houses and meat processing facilities are low-income people of color. Many of these workers are undocumented immigrants, who are often unaware of U.S. labor laws and their occupational rights and are made to work in unsafe conditions by the large meat processing corporations for which they work. While small sustainable meat farms like Marion Acres present a much healthier, responsible environment for workers, farmers, and animals, it seems irresponsible for those small farms, and for Modern Farmer, to dress-up slaughter in a way that romanticizes it while ignoring the brutal challenges faced by many of their fellow professionals.

Granted, there is a difference between agricultural professionals and the women who come to Marion Acres for a day on the farm. The “Ladies Chicken Harvest” is ostensibly an event for consumers seeking a farm “experience.” I don’t want to discount the value in that, nor bash what was likely a fun and even educational activity. But I think it’s important for consumers, small farms, and agricultural-themed publications like Modern Farmer (which for the record, has featured some thoughtful, informative articles, specifically related to women in the meat industry, see Victoria Bouloubasis’ “Lady Butchers Grab The Knife,” from August 15, 2013) to be more mindful of the way women and people of color are represented (or not represented) in relation to agricultural labor and rural life. Women should not be portrayed as fetish, object, or dress-up doll, but in a way such that “all the women go home appreciating where our food comes from,” with mindfulness, respect, and agency.

Emily Hilliard is a folklorist and writer whose research interests center around women's creative domesticity and the intersection between traditional and experimental culture. She holds an M.A. in folklore from the University of North Carolina and her work has appeared on NPR, the Southern Foodways Alliance, and in the upcoming issue of Ecotone. She also writes the pie blog Nothing in the house.