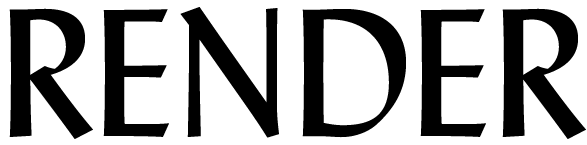

Figure 1: The sanitary inspector and police officer approach a seemingly wary Mrs. McElroy during the Piggery War while she stirs the offal she will later sell to local manufacturers and feed to her pigs. Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, August 13, 1859.

In the nineteenth century, New York City had its fair share of pigs. And this wasn’t just on the farms outside of the built-up part of the city; it was deep in the heart of bustling Manhattan. Loose or penned, urban hogs spurred a number of battles in the city and poorer women played a central role in protecting them.

Today, it is common to hear tourists and even native New Yorkers complain about how filthy New York is, but what they don’t realize is that the city is nothing like it once was. During the nineteenth century, garbage cluttered the streets, obstructed traffic, created nasty smells, and caused political battles. The upside (at least in the eyes of some) was that these piles of mainly food-based trash could feed animals if you set them out in the streets. Many poorer New Yorkers owned pigs and kept them as a source of food and income. They essentially turned unwanted waste into protein.

Not everyone saw the pigs’ ability to subsist for free on the streets of Manhattan as a boon for the city. Though New Yorkers had fought over the presence of hogs since the colonial era, the 1810s and 1820s saw a surge in interest in the hogs and their impact on the identity and health of the city. It was during the early nineteenth century that New York saw a boom in immigration and relatedly in the amount of garbage city dwellers produced. Hogs were thriving.

The city government, in turn, passed several laws that banned hogs from the densest parts of Manhattan. When they actually enforced the laws, however, they were met with stiff resistance. Notably, in newspaper accounts and memoirs of the era, authors repeatedly noted how frequently women were involved in these riots. Hogs were an important part of poor New Yorkers’ household economies and it seems likely that women were typically in charge of collecting them at night and tending to them as necessary. There were plenty of riots for a variety of causes in New York in the nineteenth century, and certainly women played roles in many of the events. The fact that authors accentuated the part played by women in the hog riots, specifically, though, shows how central they were in nineteenth-century urban agriculture.

While city leaders eventually removed hogs from the streets of the city in 1849 following the panic over sanitation during a cholera outbreak, many piggeries, or pig farms, opened up throughout the upper reaches of the city. Even these penned pigs caused debates over urban agriculture in Manhattan. Immigrant families typically ran these piggeries, where they also boiled offal, fat, and bones. They essentially collected the city’s slaughterhouse and street waste and processed what they could to sell to local manufacturers: bones to toothbrush manufacturers, button makers, and fertilizer companies; blood to sugar refiners; tallow to soap and candle makers; etc. The piggery owners then fed whatever was leftover from the boiling process to pigs that they eventually sold to local butchers.

The most organized and effective effort to get rid of these piggeries occurred in 1859, and was called the “Piggery War.” Urban agriculture was hardly respected in nineteenth-century New York—a far cry from our current embrace of backyard chickens and rooftop beehives—and this was no more evident than in the government attacks on the piggeries.

In July 1859, a newly appointed City Inspector—Daniel Delavan—helped to usher in a new law banning all piggeries and offal-boiling establishments south of 86th Street. Soon after the city government approved the law, troops consisting of sanitary inspectors and municipal police visited each piggery in what is now midtown Manhattan and warned the proprietors that if they didn’t remove or demolish all evidence of their businesses in three days, the police would return to do it for them.

When the police and health inspectors returned after the three days, they were armed with guns and clubs, as well as the kinds of tools necessary for demolishing sheds and pigpens. They expected resistance, maybe even a riot. Despite all of the war metaphors thrown around by journalists and politicians and the threats of several piggery owners, very few men fought back.

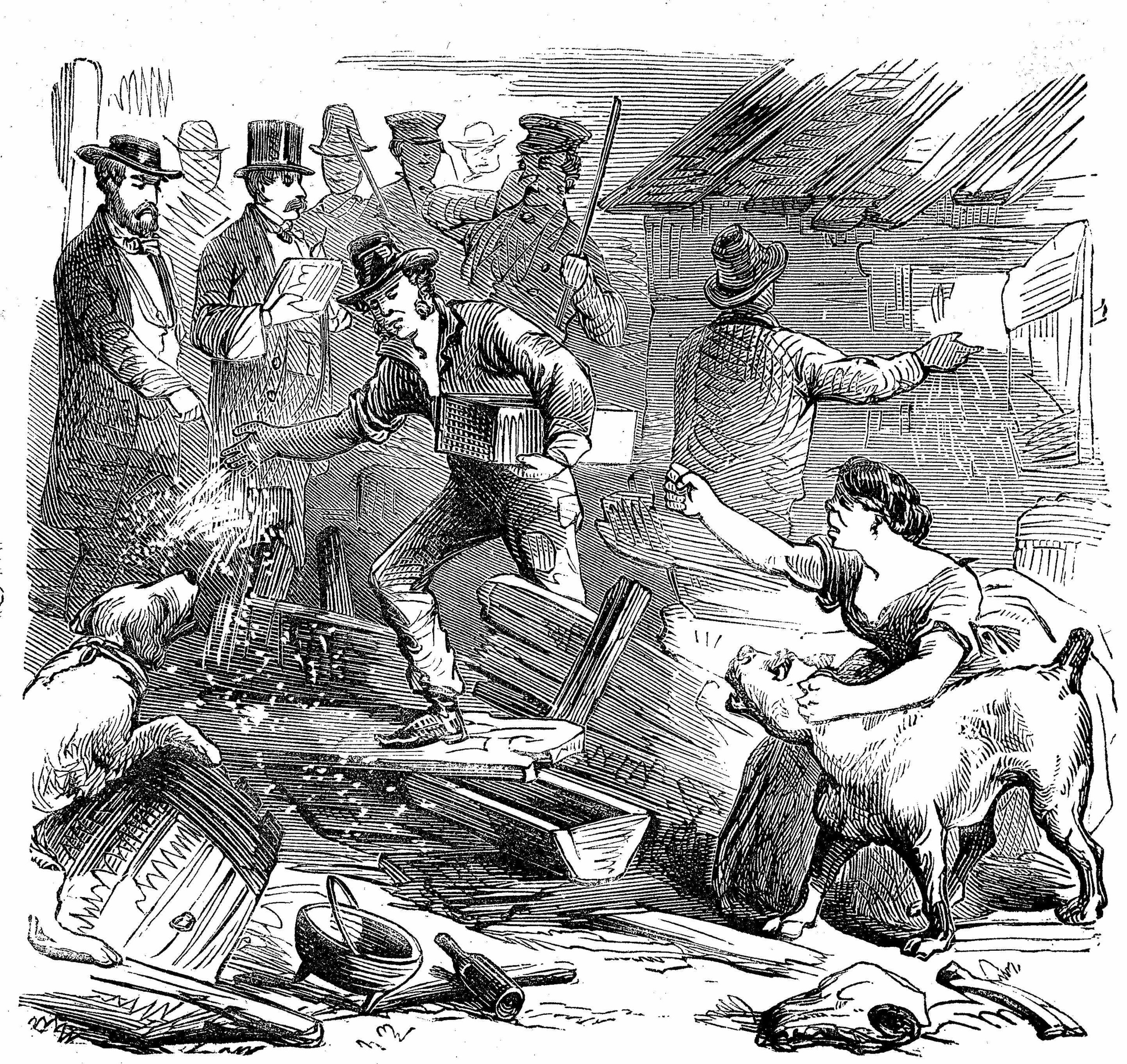

Figure 2: A piggery owner raises her fist as officials sprinkle lime over her destroyed property in an effort to disinfect it and mitigate the odors. Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, August 13, 1859.

Instead, women were actually the most violent participants in the Piggery War. Whether this was because the police were less likely to strike back and treat a female attack seriously, or because pigs were particularly important to these women, the female piggery owners took up clubs and other weapons to defend their property.

The New York Herald delighted in describing a “large squarely built German woman” who attacked a policeman with an enormous tin pot after he seized her hog. The newspaper emphasized the comic nature of the encounter, describing how the clobber made the policeman “see stars” and that the whole event amounted to a “thrilling scene” filled with the woman and her husband shouting in German, the policeman calling for help, and the shrill squeals of the pig trying to escape his grasp.

The fact that journalists and likely their readers poked fun at Irish “biddies” hiding pigs in their dressers and under their beds accentuated the gulf between classes and ethnicities in New York during this time. The Irish and German women whose families owned these piggeries seemed so incredibly different from New York’s middle- and upper-class women who would have been ashamed to resort to violence, let alone allow livestock into their parlors or bedrooms.

These accounts, though, also point to the continued importance of women to urban agriculture and the creation of urban food. From the hog riots of the early nineteenth century to the Piggery War of 1859 and beyond, women played a central role in the protection of their families’ agricultural property and livelihoods.

Catherine McNeur is Assistant Professor of Environmental History and Public History at Portland State University. Her book, Taming Manhattan: Environmental Battles in the Antebellum City will be published this fall by Harvard University Press and is available for pre-order at Powell’s, Amazon, and Barnes and Noble.

"The Hog War—A Policeman in a Tight Place," The New York Herald, 11 August 1859.