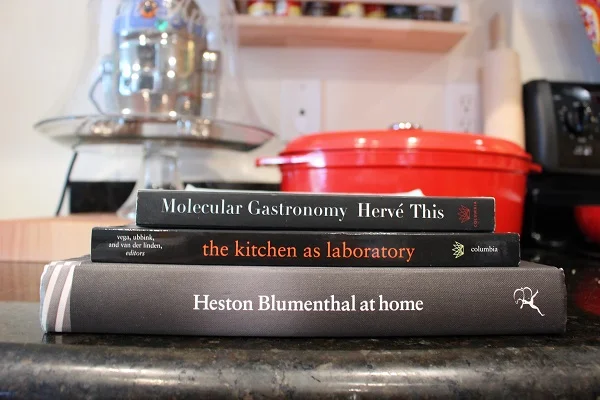

There are few things I love more in this world than accessible, fun, scientific explanations of food, cooking, and flavor. You already know that I’m a big fan of Harold McGee’s On Food and Cooking, but there is a wealth of information outside of that amazing tome, and we’re discovering more and more each day.

Not every book is a good fit for every reader, so we here at RENDER have reviewed three of varying levels of accessibility. Hopefully one of them will find its way on to your bookshelf or into your kitchen.

The Classic: Molecular Gastronomy: Exploring the Science of Flavor by Hervé This

When people think “molecular gastronomy,” they usually think of spherified juices and cocktails you inhale; not a perfectly cooked egg. At its core, molecular gastronomy is less about making ice cream with liquid nitrogen and olive oil powder with maltodextrin; it’s about understanding food and cooking on a molecular level, allowing us to perfect techniques and debunk old myths.

(Fancy maltodextrin powders never win Chopped anyway, the judges are always kind of like “Uh, this is kinda gross.”)

Known by most as the “father of molecular gastronomy” and “the man who unboiled an egg,” Hervé This wrote Molecular Gastronomy in 2005, years after coining the term with fellow scientist Nicholas Kurti.

Though physical chemists aren’t usually known for their elegant prose, This manages to be almost poetic in describing egg coagulation, flat globules in milk, and bacteria in hard sausages.

The Pros: This thought of food in terms of chemical mixtures (which it is) but that doesn’t make him a cold and calculating chemist. His love for food and cooking is apparent in each concise chapter (This manages to bestow a wealth of information in each 3-4 page chapter); his goal of educating and enlightening clear in every paragraph.

This does not drone on for pages, boring the reader with dry, emotionless facts and graphs. He is able to communicate scientific concepts succinctly and never loses sight of the matter at hand: FOOD. After explaining that the old spoon in the bottle trick does not, in fact, keep champagne from going flat, he negates the need of such a discussion by declaring that “Once you’ve opened a bottle, finish it off!”

The Cons: Molecular Gastronomy may not appeal to those who hated every moment of every science class they ever took. Though This describes the molecular aspects of food in an accessible and engaging way, basic scientific nomenclature is still employed.

Highlight: Chapter 3, which is all about hard-boiled eggs, makes one truly appreciate how complex the seemingly simple act of boiling an egg can be.

The Compilation: The Kitchen as Laboratory: Reflections on the Science of Food and Cooking

I was really excited about this book. It has a really cool looking beaker on the cover, in which appears to be some shrimp and thinly-sliced zucchini. It’s pretty sleek looking, really.

Compiled by César Vega, Jobb Ubbink and Erik van der Linden, this book reads like a compilation of slightly informal journal articles, which may be good or bad, depending on who you are. Containing a variety of essays and recipes from various artists, it’s a bit of a grab bag in terms of accessibility.

The Pros: The science within The Kitchen as Laboratory is legit. If you are a lover of graphs and the scientific method, this is the book for you. The essays are thorough and the language precise and the recipes are surprisingly easy to follow.

Also, there are poems.

Cons: Parts of this book are oh so boring. I like science, but even I had a hard time with some of the chapters. Since it is a compilation, the level of accessibility varies from essay to essay, but it is clear that the book was written by scientists and not science communicators. This isn’t to say that every essay is completely inaccessible, but some authors are more engaging than others and there’s no way to tell before reading the essay.

Highlight: The chapter entitled “Ice Cream Unlimited” (Chapter 17), which features recipes for Cherry-Kriek Sorbet and Tzatziki Ice Cream.

The Showstopper: Heston Blumenthal at Home

Though Blumenthal dislikes his work being characterized as “molecular gastronomy” explaining in a feature on The Guardian that “Molecular makes it sound complicated, and gastronomy makes it sound elitist.” In spite of his preference, Heston and his restaurant – The Fat Duck – are firmly associated with the term; the dude loves liquid nitrogen and sous-vide. Loves it.

At Home features some adapted Fat Duck favorites (such as the Bacon and Egg Ice Cream) but also includes recipes for staples such as compound butters, stocks, and mayonnaises. Don’t be fooled by the seemingly “simpler” recipes; this is not a simple cookbook.

This is a beautiful, informative, ever so slightly pedantic tome perfect for the home chef who wants to take it up a notch.

The Pros: First of all, the images alone make the book worth picking up. The photo accompanying a recipe for Pea and Ham Soup somehow manages to look elegant and slightly sinister while the cheese-centric photos are downright erotic.

Each chapter begins with a short historical/scientific treatise concerning the subject at hand. The chapter on cheese explains the process of cheese making, offers tips on how to cook cheese to perfection, and finally explains what those little white crystals on parmesan are. (Surprise! It’s MSG!)

Though some may be initially annoyed by this, Blumenthal supplies most measurements by mass and – be still my chemist’s heart – the metric system. This eliminates the tiny amount of guesswork that is involved when dealing with volume, and helps the reader produce consistently good dishes each time; 100 grams is always 100 grams.

In addition to beautiful photos, educational prologues, and a superior system of measurement, the recipes are just plain fun. Whether through presentation or flavor Blumenthal’s dishes are truly creative. His Garden Salad with Sauce Gribiche looks like an actual vegetable garden, finely walking the line between “utterly charming” and “maybe a little too whimsical.”

The Cons: These recipes are not of the budget variety. Whether through specialty equipment (pressure cooker, blow torch, a sous-vide constant temperature water circulator) or specialty ingredients (dry ice, smoking chips, all of those British foods that are hard to find this side of the pond) one can end up spending quite a bit per recipe. And never let it be said that Blumenthal skimps on quality; vanilla extract is never suggested, only the bean, though it’s hardly fair to call that a “con.” I’ll take mild fussiness over Sandra Lee –style shenanigans any day.

Highlight: Whiskey Ice Cream. BECAUSE WHISKEY AND ICE CREAM.

I leave you with a recipe. Because July 4th is fast approaching, I thought it appropriate to give you something you could take to a BBQ. Let others bring plebeian chips and dip. Let lesser ones bring watermelon. You are bringing Choucroûte, sauerkraut’s more sophisticated cousin.

Choucroûte

Choucroûte is a savory, slightly less pungent variety of pickled cabbage, elevated with butter-sauteed onions and Gewürztraminer wine. Toss it with potatoes for a potato salad that is light or heavy on flavor (and vitamin C) or use it to top grilled sausages. Everyone will be very impressed by your worldliness and culinary skill.

Choucroûte (adapted from Heston Blumenthal at home)

You will need:

100 g unsalted butter

400 g peeled and finely sliced onions

1 clove of garlic, smashed and chopped

1 tsp juniper berries, wrapped in a muslin bag

300 g Gewürztraminer wine

50 g white wine vinegar

Salt and pepper

1 cabbage (Savoy is suggested, but I could only find green)

1 tbsp groundnut or grapeseed oil (I omitted this and used the residual bacon grease)

30 g smoked bacon lardons

1. Melt the butter over medium heat and sweat the garlic, onions, and juniper berries until onions are soft and lightly colored (about 20 minutes). Discard juniper berries.

2. Add wine and reduce by about a third. Add vinegar and reduce for 5 minutes. Season with salt and pepper and remove from heat. Strain onions and reserve both liquid and onions. (I’m not sure why, as you add them all back together in the end.)

3. Cut cabbage in half and remove tough core. Slice leaves into thin strips (5 mm, to be exact).

4. If you are using oil, heat and add bacon. Cook bacon until lightly colored and drain on paper towels. Cook cabbage in oil and bacon grease for about 7 minutes. Mix in onions, liquid, and bacon and cook for an additional 5 minutes.

5. Season with salt and pepper to taste before serving.

Be the hit of your respective 4th of July party.