Although we believe that every month of the calendar year should be Women's History Month, we're taking advantage of the specially designated month to showcase some of our favorite female food-related events in history. You may recognize some of these women and happenings, but we hope that at least a couple are new to you and expand your knowledge of the deep connection between women and food!

Women's March on Versailles, 1789

Since women in most cultures have been historically charged with providing food for their families, food shortages and lack of access to food have brought about many instances of collective protest and actions led by women. One particular example of this is the Women's March on Versailles, the culmination of demonstrations organized by women angered by the high food prices and scarcity of bread at Parisian markets. To get their point across, these women ransacked the town of its weapons and took their complaints to the Palace of Versailles. By the time they reached the palace, the mob numbered in the thousands and enabled them to successfully besiege King Louis XVI and his family. The King begrudgingly returned to Paris, where negotiations between the people and monarchy began. Women have always been at the vanguard of popular movements, and will continue to be as long as they are responsible for family provisions. Just one example of how a little food and a lot of women can change the course of history!

For further reading on women and consumer rebellions: David Barry, Women and Political Insurgency: France in the Mid-Nineteenth Century; Harriet Applewhite and Darlene Levy, Women and Politics in the Age of Democratic Revolution.

Consider the Oyster is published, 1941

"An oyster leads a dreadful but exciting life.

Indeed, his chance to live at all is slim, and if he should survive the arrows of his own outrageous fortune and in the two weeks of his carefree youth find a clean smooth place to fix on, the years afterwards are full of stress, passion and danger.

He — but why make him a he, except for clarity? Almost any normal oyster never knows from one year to the next whether he is he or she, and may start at any moment, after the first year, to lay eggs where before he spent his sexual energies in being exceptionally masculine. If he is a she, her energies are equally feminine, so that in a single summer, if all goes well, and the temperature of the water is somewhere around or above seventy degrees, she may spawn several hundred million eggs, fifteen to one hundred million at a time, with commendable pride."

MFK Fisher's work is perhaps the most famous book about oysters ever to be written. The books she penned prior (including Serve it Forth) changed culinary writing and introduced the style that you find today.

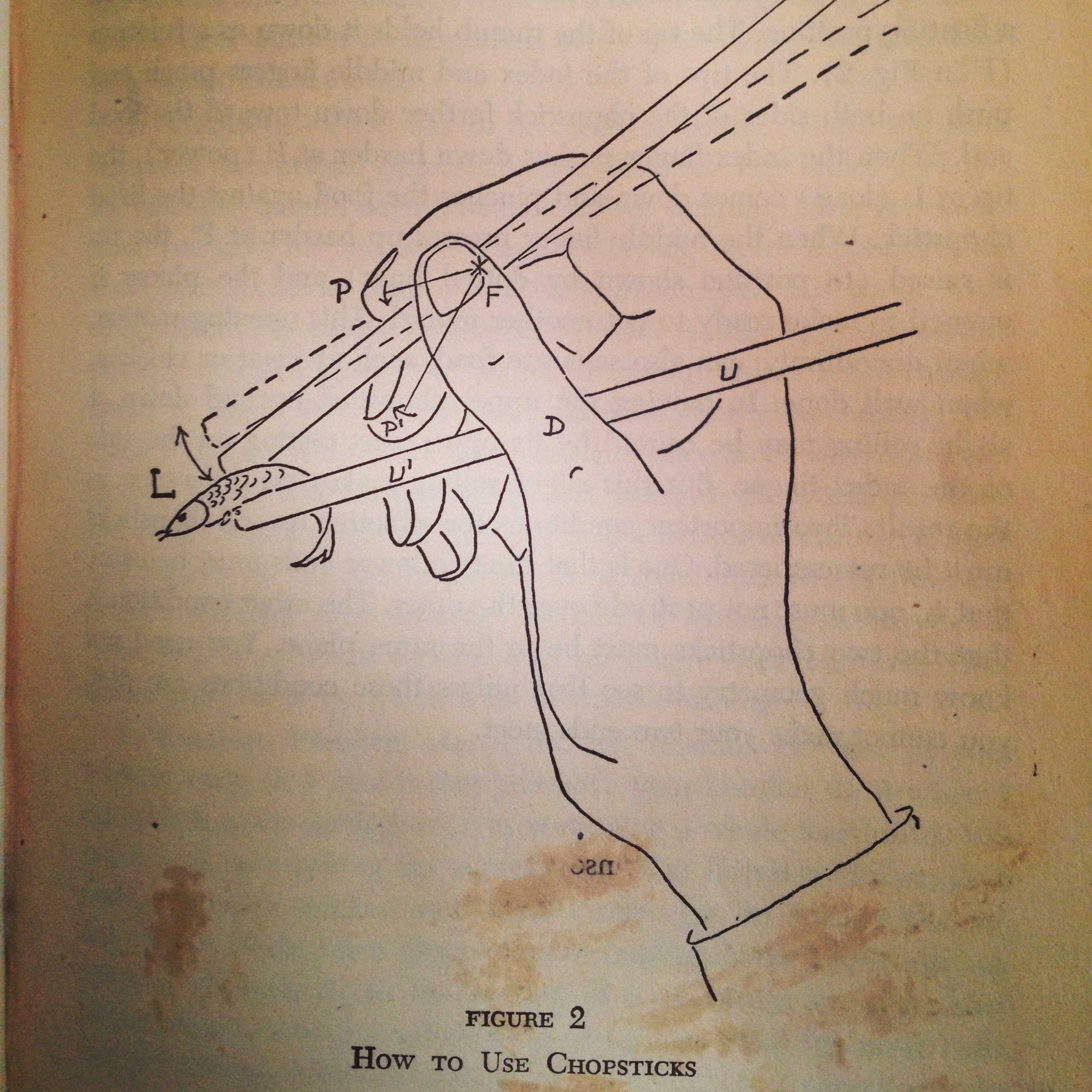

Buwei Yang Chao instructs the United States on Chinese cooking, 1945

"How to Cook and Eat in Chinese,'' by Buwei Yang Chao is considered to be the first attempt at bringing authentic Chinese cooking techniques and recipes to the non-native population in the United States. Buwei Yang Chao was a medical physician who learned how to cook while working in Japan, where she found the food completely inedible and thus learned how to make her own meals. Not only does her book include tien-hsin (or dim sum) recipes that shaped the way Westerners consume Chinese food, but the common stir-fry technique, of which many Americans are familiar with, arose from a difficult translation of "ch'ao" into "big fire-shallow-fat-continual-stirring-quick-frying-of-cut-up-material with wet seasoning." While the book itself was mostly written in its English version by Yang Chao's husband, she played a major role in its genesis and the book's influence on American Chinese cooking and vocabulary is undeniable.

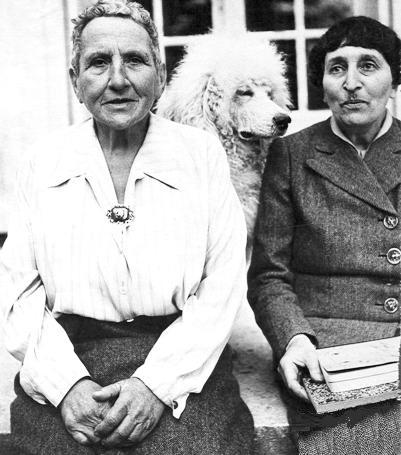

Alice B. Toklas publishes the first pot brownie recipe, 1954

Alice B. Toklas was the life force behind writer Gertrude Stein, member of the avant-garde circles in turn of the century Paris, and friend to many American writers that frequented the Stein-Toklas household. She was Stein's partner and muse, but also her cook, secretary and editor. Her cook book, the Alice B. Toklas Cook Book, was published in 1954 after Stein's death. Half memoir, half recipes, the book was hugely referenced in the 1960s because of one particular recipe, the "Hashish Fudge." While later admitting that the recipe was given to her by a friend, Brion Gysin, Toklas continues to be associated with the pot brownie. This particular recipe from her cook book contains fruit, spices, nuts, and Cannabis as ingredients, and gives the reader suggestions on where to find the illegal substance. She goes on to say that the fudge is "easy to whip up on a rainy day" but cautions the reader that eating more than two pieces will result in hysterical fits of laughter and wild floods of thoughts on "many simultaneous planes."

Despite this more whimsical legacy, Toklas is also remembered and revered by many LGBTQ organizations, and has recently become the namesake for a network of women in the hospitality industry, The Toklas Society.

Jessie De La Cruz joins the United Farmworkers of America (UFW), 1965

Jessie Lopez De La Cruz was a prominent member of the United Farmworkers of America union, and one of its first female organizers. She participated in the grape boycotts, taught English to migrant workers, and testified to outlaw the use of the short-handled hoe. She was motivated to join after Cesar Chavez visited her home and convinced her that ordinary people had the power to do extraordinary things. De La Cruz continued to attend rallies and protests well into her senior years, fighting for justice on the front lines. She died on Labor Day (September 4th), 2013. She was 93.

Chez Panisse opens in Berkeley, California, 1971

Alice Waters pioneered the farm to table movement by adamantly requiring the food served at her California restaurant, Chez Panisse, be organic and locally grown. An activist and leading member of the Organic Food Movement, Waters is considered by many to be one of the most influential figures on American food. When Chez Panisse was opened in 1971, it was mostly a place for Waters and her friends to congregate and socialize. In her attempts to serve only the highest quality and freshest ingredients, she began to build a network of local farmers, culinary artisans, and specialty producers that could provide the restaurant with finer goods. Waters' approach to cooking at Chez Panisse has made an impact on several of the world's top chefs, including Suzanne Goin and Rose Gray.

Edna Lewis receives the inaugural James Beard Living Legend Award, 1995

One of eighteen children and the granddaughter of an emancipated slave, Edna Lewis was born in rural Virginia in 1916. She was the first person to ever receive the James Beard Living Legend Award for her contributions to American culinary history, particularly in terms of Southern cooking. She first cooked in Manhattan's Café Nicholson for some of the most prominent bohemian artists of the time including William Faulkner, Marlon Brando, Truman Capot, Gloria Vanderbilt, Marlene Dietrich, and so on. She cooked there throughout the 1950s, and then turned to publishing cookbooks. Backed by Judith Jones, Julia Child's cookbook editor, Lewis published The Edna Lewis Cookbook in 1972, followed by The Taste of Country Cooking in 1976. After retiring from cooking in the 1990s, she went on to co-found the Society for the Revival and Preservation of Southern Food, a precursor to the Southern Foodways Alliance (SFA). She received numerous awards and honors in recognition of her influence on and preservation of American cooking, including the James Beard Living Legend Award in 1995. In 2006, Edna Lewis died peacefully at age 89.